Video of Daniel Prude’s restraint and subsequent autopsy likelywill be the centerpiece of decisions about whether officers will be charged.

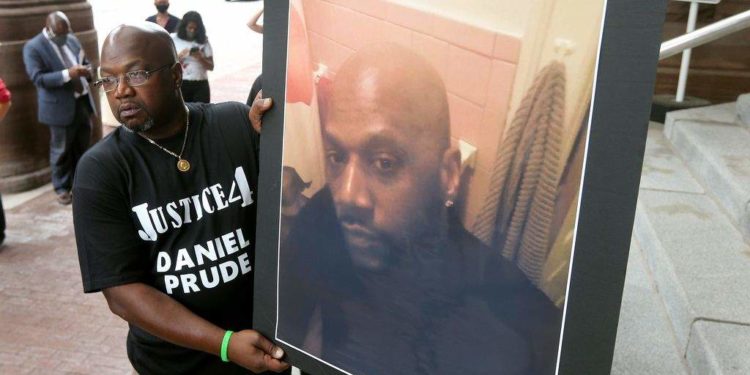

ROCHESTER, N.Y. — Only days ago, the homicide of Daniel Prude became public.

The news sparked anger. It sparked peaceful protests mixed with scattered vandalism. It sparked finger-pointing among public officials.

While the protests and public dialogue may lead to reforms, the video of Prude’s restraint and the subsequent autopsy likely will be the centerpiece of decisions about whether police acted criminally with his death.

And there is much in the video and the autopsy, even with its granular medical detail, that will surely be questioned and challenged.

Among the questions:

Did the police use restraint techniques that were accepted within law enforcement circles, or instead was it pressure of the sort known to be dangerous and even deadly for mentally troubled or drug-using individuals held in a prone position?

Does the use of the term “excited delirium” — both by emergency workers who responded to the scene Jefferson Avenue, where police constrained Prude, and again in the autopsy — stand as a rationale for the police restraint? Or is “excited delirium” a term that lacks medical foundation, used as an explanation and excuse for the deaths of civilians at the hands of police?

Was Prude’s erratic behavior — he was naked and ranting, while not acting violently — clear proof that mental health professionals should have been summoned immediately? Or, instead, did police think he was too medically and mentally fragile for such an intervention, and medical workers needed to be the first to be called?

The Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, part of the USA TODAY Network, spoke to current and retired medical examiners and pathologists, lawyers, mental health experts, former police officers, and former city officials for insight into these questions. Many spoke on the record, while some chose not to do so.

Even some of those often hesitant to question police actions acknowledge that they are disturbed by the public revelations thus far.

“This is the worst video I have ever seen,” said Linda Kingsley, who served as Rochester Corporation Counsel for 12 years and now teaches local and state government law at the Albany Law School.

“The basic concept of the law and training of every police department in this country is you only use the necessary force and you de-escalate when possible,” she said.

Was restraint needed?

When police encountered Daniel Prude, 41, in the early morning hours of March 23, he was naked and wandering Jefferson Avenue.

Earlier, his brother tried to have him admitted to Strong Memorial Hospital for mental health purposes, but he was not held overnight. The hospital has said it acted properly; Prude’s brother, Joe, has questioned why he was not kept there.

Videos show Prude largely complying with police as he is handcuffed, and he lies and sits on the street, continuing to rant, often incoherently. He also is bleeding from apparently breaking a window or windows on the street.

At some point, Prude said he had coronavirus; police later covered his head with a hood, commonly known as a “spit hood,” to protect officers should he spit toward them.

At one point, awaiting medical workers, at least three officers physically restrain him, pinning him to the ground. The autopsy clearly attributes Prude’s death a week later to the loss of oxygen he suffered; the death was ruled a homicide.

“You can see in that video his voice changes, his breathing change … and they still don’t get off him,” Kingsley said.

There is a wealth of research showing the hazards of restraining individuals in a prone position who may be undergoing physical or drug-induced trauma.

Prude also had the hallucinogen phencyclidine, or PCP, in his system. PCP can bring on violent responses, but Prude did not display any hint of physical aggression in the video.

While handcuffed, he asked for a gun repeatedly. He also asked for mace, gloves, $70 and an undefined “it.”

“When asphyxia is put down as a cause of death, it means that the body was deprived of oxygen, and that could cause unconsciousness and death,” said Dr. Homer Venters, a physician, epidemiologist and the former chief medical officer of the New York City Correctional Health Services. “We have decades of evidence that physical restraint and use of physical force can cause asphyxia and deaths from asphyxia.

“One of the things I’ve seen in cases that I investigated is that officers may engage with somebody who doesn’t follow their command … and at some point the (police) response is a response that should be reserved for a real safety threat to their lives or the lives of another person.”

Dr. Mary Jumbelic, a former Onondaga County medical examiner, said the spit hood may have obscured what the police could see about Prude’s worsening condition during restraint.

“He had a ‘spit cover’ on, which allows respiration but doesn’t allow the officers to see his face for assessing his well being,” she said. “The prone position itself can cause limitation of air movement into the lungs and then, when you add physical restraint in, makes a person vulnerable to asphyxiation.

“He vomited and that tells me he may have aspirated causing further irritation of the airway and (another) reason for hypoxia,” which is the deprivation of needed oxygen, Jumbelic said.

Also, she said, the PCP could have exacerbated the likelihood of asphyxiation, which the autopsy also notes.

“With people that use drugs like that, I’ve seen multiple circumstances when they are vulnerable to asphyxia and they’re vulnerable when being put in a prone position.”

In 1995, the Department of Justice warned about the dangers of what is known as “positional asphyxiation,” which most often happens when an individual is restrained in a prone position, said Keith Taylor, a former supervisor of the New York City Police Special Weapons And Tactics, or SWAT, unit.

“Prone restraint, due to the health challenges involved, is not advisable to do,” said Taylor, who now is an adjunct assistant professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. “There may be circumstances where it’s unavoidable and the officers have no other choice.

“Once the person is restrained, once they are cuffed … put them on their side.”

Union defends restraint method

At a news conference Friday, Rochester Police Locust Club Union President Mike Mazzeo said the officers restraining Prude appeared to adhere to training procedures, and that an internal police investigation had not raised any red flags about the restraint methods.

That investigation, conducted by police criminal investigators, was halted when the Attorney General’s Office took over in mid-April. An executive order from New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo mandates that the Attorney General investigate incidents in which unarmed civilians die at the hands of police.

“An officer doesn’t have the ability to go off-script,” Mazzeo said. “They have to follow protocol and do what they are trained to do.

“To me, it looks like (the officers) watched training and followed it step by step. If there’s a problem with that (procedure), let’s change it.”

Former Rochester Corporation Counsel Kingsley questioned how any training would include the restraint of a naked man who posed no threat, and why more attention was not paid to his condition.

The police policy tells officers to closely monitor individuals who are restrained and appear to be emotionally disturbed or under the influence of drugs. The restraint and force should be based on the risk to officers or the individual or property.

“This guy wasn’t a criminal,” Kingsley said. “Yes, apparently he broke a few windows. But they were looking for him because he was an EDP (emotionally disturbed person). … He was naked and he was unarmed and he was cuffed without any resistance.”

Kingsley said she thought the officers, for the first minute shown on the video, handled Prude with respect and concerns for his well-being. But then the responses from some devolved into jokes and a lack of attention once he was handcuffed and hooded. The ambulance workers also at first discuss Prude’s condition with police, she said.

“They’re chatting rather than seeing if they can help while this guy is clearly in respiratory arrest.”

‘Excited delirium’ and death

Prude’s autopsy says he showed signs of “excited delirium,” which has been a term for a combination of mental and physiological actions and symptoms, including agitation, aggressive behavior, profuse sweating, and claims of bouts of unusual strength.

But that term, which many critics say is not a medical diagnosis, has become controversial in recent years.

Dr. Venters, who headed the medical care operations for the New York City jails, said that many of the fatalities in which “excited delirium” is highlighted occur at the hands of police or with inmates in confrontations with corrections workers.

Disproportionately, he said, people of color and people with mental illness are the victims in those cases.

“My grave concern is that this term, ‘excited delirium,’ is used to absolve law enforcement of responsibility” with the deaths, he said.

With the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis, a homicide that triggered national protests against police brutality of Black citizens, a police officer can be heard on video saying, “I am worried about excited delirium or whatever.” The police and a paramedic at the Prude incident also talk of “excited delirium.”

Dallas, Texas attorney Geoff Henley represents the family of a man who died at the hands of police in 2016 in circumstances similar to Prude’s and Floyd’s deaths.

“Excited delirium, number one, is a term that has multiple definitions,” Henley said.

“Excited delirium simply just means a description manifested by conduct of someone in an agitated mental state,” he said. “The cops like to assert … that it is a cause of death, that the excited delirium is what killed them. They like to claim that they are, in essence, killing themselves because of excited delirium.”

But former City Corporation Counsel Kingsley said, whether excited delirium is legitimate or not, the signs that an individual may be in that state is a further indication of the need for cautious and medically sensitive restraint.

“You can’t have it both ways,” she said.

Former Onondaga Medical Examiner Jumbelic said that “excited delirium as a term isn’t very helpful.”

Instead, she said, the focus should be on the effects of the restraint, the PCP presence, and other possible contributors to the death.

Need for mental health assistance

When police sought out Daniel Prude on March 23, his mercurial mental state was no secret. His brother called police and told them of Daniel’s strange actions.

But, while Prude was handcuffed and restrained, there was no apparent effort to reach out for mental health assistance.

On Thursday, Rochester Mayor Lovely Warren suspended seven officers who were at the scene and said she wants to bolster mental health responses to similar incidents. Critics of the mayor have challenged her claims that she did not know that Prude was a homicide victim until August, and that her staff and the police kept her in the dark for the months after the fatality.

Calls to “defund the police” have coincided with a push for police to utilize mental health professionals. The movement in part maintains that public funds for law enforcement could be better used if shifted toward mental health treatment.

Former New York City SWAT supervisor Taylor said that police interactions with mentally troubled people has long been a law enforcement trouble spot.

“There’s not a uniform way to address it,” he said. “I think it has to be addressed at the national level, to have training requirements.”

The Rochester Police Department, like many, has some officers who undergo “crisis intervention” training to help them deal with mentally ill individuals.

But the problems persist at most law enforcement agencies, Taylor said.

“The normal (police) processes don’t work” in confrontations with mentally troubled people, he said. “They’re not going to listen to your commands. They may be physically compromised. Their health status may result in a negative outcome.”

Taylor pointed to 2015 research from the nonprofit Treatment Advocacy Center showing that people with untreated mental illness are 16 times more likely to be killed during a police encounter than other civilians approached or stopped by law enforcement.

“That’s screaming for intelligent responses by the mental health community in cooperation with law enforcement agencies,” he said.

Still, Taylor said, “you can’t take mental health professionals into every situation, particularly where there may be violence involved.”

With Daniel Prude, police may have determined that a quick medical response was more necessary than an attempted mental health intervention.

“One of the things that this case highlights is police should not be making mental health calls,” said Dr. Sarah Vinson, an associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at Morehouse School of Medicine. “It looks like he had broken a window or something but he clearly was not presenting an acute risk to someone’s health. He was most at risk.

“They weren’t the appropriate people to respond, and that was demonstrated by them laughing at him. The actions they took — the use of force when it clearly wasn’t necessary — just emphasizes the root issue that we should not have police responding to mental health calls.”

People of color, if struggling with mental health issues, are more likely to find themselves confronting an arrest instead of needed treatment, Vinson said.

“We know that behaviors by certain people are more likely to be criminalized,” she said.

And, she cautioned, even a supposedly well-intentioned treatment program can be racist in operation. Court diversion programs, which try to route addicts and the mentally ill into treatment, have shown a propensity to accept more white people than Black people, Vinson said.

“Whenever you superimpose something on a racist system, it’s not going to fix the problem,” she said.

Society has too often looked to police as the answer for problems they are not well trained or suited to resolve, Kingsley said. “There is not a cop on the street who has not dealt with a ton of mentally disturbed people,” she said.

Kingsley, who was the city’s lead lawyer under former Mayor Bill Johnson, said she hopes there is some way something positive can come from the tragedy of Daniel Prude’s homicide.

“I’ve lived in this city for 26 years. I love this place.

“And now we have become a national spectacle.”

Source link