Books

Bliss talks about how he became the artist behind — and a character in — the bestseller “Number One is Walking,” Steve Martin’s film career memoir.

Harry Bliss has come a long way from Philadelphia.

“I was on welfare when I was in Philly,” Bliss recalled last week, speaking from his home in Cornish, New Hampshire, about his time studying at the University of the Arts. “I mean, I was that poor for at least a year-and-a-half.”

But these days, Bliss, 58, is a longtime New Yorker cartoonist with thousands of gag panels and several dozen covers under his belt — and more recently, he’s the collaborator with comedy legend Steve Martin on two books: 2020’s gag cartoon collection “A Wealth of Pigeons,” and this year’s bestselling “Number One is Walking,” a series of comic book-style illustrated anecdotes about Martin’s film career.

Not only that, but Bliss and his dog, Penny, are even characters in the book, pictured as the (mostly) willing audience for Martin’s Hollywood stories.

“I just thought it was a nice segue, a kind of establishing opening shot,” Bliss says of the technique. “Maybe there’s one of Steve pouring wine in my living room, and that’s actually my living room, that’s my fireplace, and Penny’s there.”

It’s a scene he probably couldn’t have imagined back in his University of the Arts days, or even during his early years at the New Yorker.

“I think my first year I did five covers, which was great — I was going to declare bankruptcy during that time,” Bliss recalls. “I mean, I was making a living, but I still owed a lot of money in student loans … But over the next few years I saved up enough money to pay off most of my loans. I lived in a basement apartment like a troll, you know, ate very frugally, and worked my ass off for the magazine.”

And now, he’s working it off with Martin, a fortuitous partnership he described during a recent interview with Boston.com and Strip Search: The Comic Strip Podcast.

Some responses have been edited for length or clarity.

Boston.com: So how did this collaboration with Steve Martin come about?

Harry Bliss: His wife was a fact checker at the New Yorker, and so I’m assuming he was having dinner with a couple of people from the magazine, this was probably four or five years ago. I wasn’t there, but my cover editor, Françoise Mouly, was there, and during that dinner Steve probably just said, “I have a couple of cartoon ideas” — and Françoise suggested me.

After that I think he made an email introduction, and then we just started emailing back and forth. He would send gag ideas — I don’t think we spoke on the phone for a couple of months. But in the beginning Steve would email me a LOT. [laughs] He was really sending a lot of ideas. Which was funny, because sometimes the ideas would come in at like 4 a.m. He’s, like, staying up late, trying to be funny and think of cartoons.

So what’s the collaboration process like? Does he just send a gag line without any context, and you have to think about how to illustrate it? Or does he give you some sort of stage directions?

Well, in the beginning he did give me some stage direction, and then he learned that he didn’t really have to. Because at a certain point I would push back and say, “You don’t have to give me direction because I can feel this out and I get the idea.” And it was fairly unspoken. I mean it just happened.

But [at first] he would send me the full idea. Here’s an example of one of Steve’s cartoons. He would say, “It’s a genie convention,” like genie in a bottle. “Overhead shot, Las Vegas convention space, just genies everywhere.” And then he would give me lines for each genie, like funny lines that they would say to each other … But I just thought, are you high? There’s way too much work in that. There’s no way I’m going to do that. [laughs]

But it was funny. The idea, I laughed at. I clearly remember reading that — I was up in bed, and I read it in the morning, and I thought, that’s a funny setup. But it wasn’t possible to do in a single panel.

A lot of times I will send him a drawing that is in need of a caption. Last time he sent me three different ideas [in response], sometimes they’re all good, I don’t know what to choose. And sometimes none of them are good, and then I’ll be like, I’m not sure, there’s a seed in this one, and then he’ll try again. And then I’d say 15% of the time we just let it die, we just don’t do it. It just doesn’t work. It’s like an unspoken thing. We just don’t communicate after that. [laughs]

So there are occasions, then, where you’re in the position of having to tell Steve Martin that he’s not funny enough.

[laughs] Well, it’s Steve getting the language of the gag cartoon, and he — you know, he learned to play the banjo, and it’ll take him some time to learn this, I suppose. But he’s a quick learn. There’s been a couple of times where I’ve been like, visually that’s not gonna work. But it’s pretty rare.

So in the new book you did with Steve, we’ll see — in sort of a comic book style — you and your dog Penny with Steve, you’re asking him questions, he gives you answers, and the anecdotes about his film career sort of flow from there. How much of that really happened? Was he jetting into New Hampshire, and you’d walk around in the woods and listen to his stories?

Not at all, no. [laughs] He wouldn’t know what to do out here.

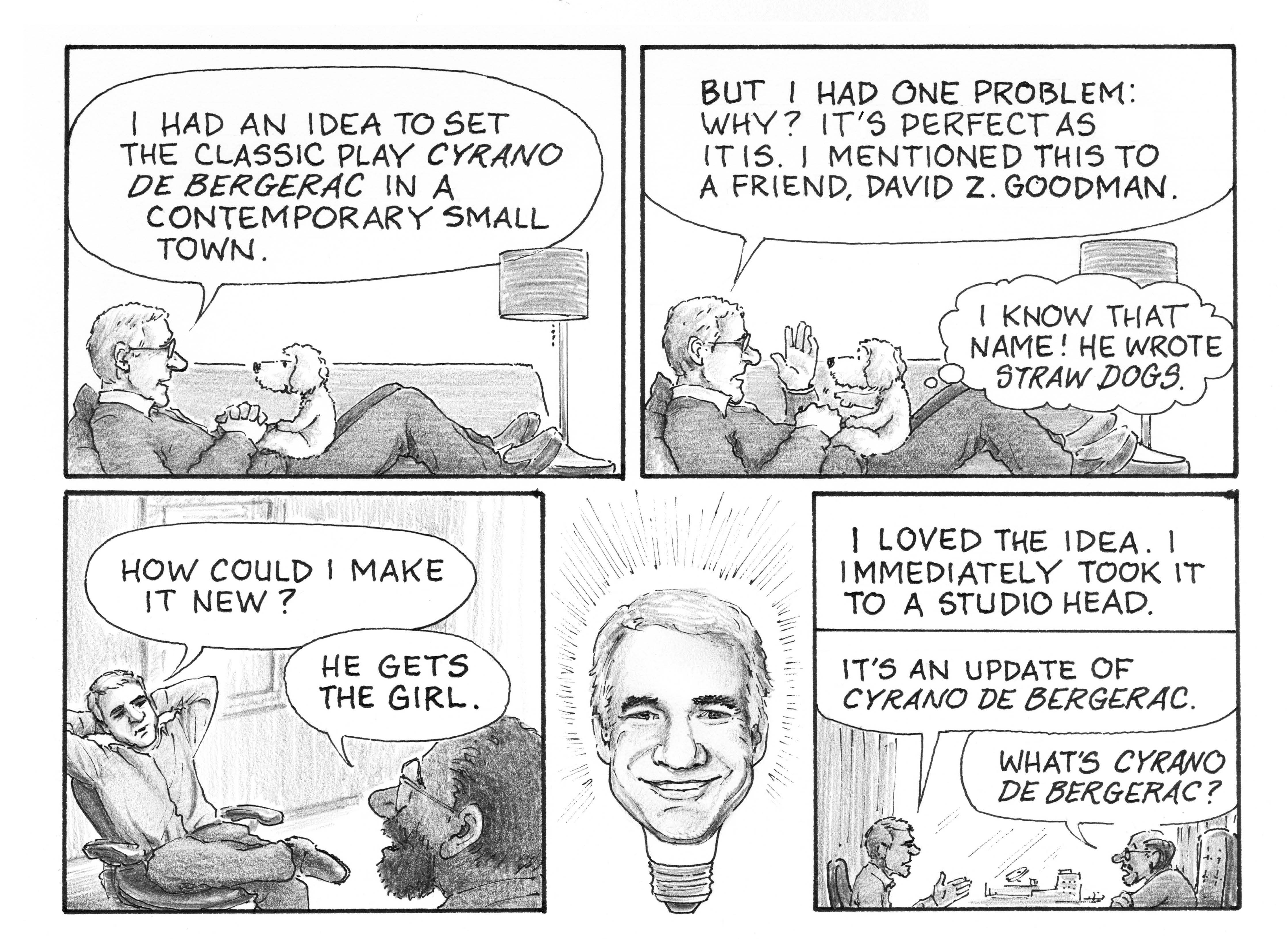

It’s weird how that happened — I just did it! I mean, I think that maybe we had a discussion at some point. But this sort of way to move into those anecdotes was [something we started] in the first book [“A Wealth of Pigeons”]. In those comic strips in the first book we did, it was Steve talking to me. And Penny was always in those, too.

Penny, she knows films. That was Steve’s idea — have Penny say, “Oh, that guy wrote ‘Straw Dogs’!” [laughs] But that’s some of the most fun for me, to draw me and Steve and Penny … There’s something very sweet about that, and just nice.

It really works for the book — it’s a great way to ease into those stories and to feel like you’re reading a narrative.

It’s also like a running [gag] … like in one of the anecdotes they’re on a boat, I think when he’s talking about the film “All of Me” with Lily Tomlin, and Penny’s fishing while he’s telling the anecdote. And during the telling of the anecdote we cut back to Penny catching a fish, and then at the very end she’s fileted the fish up, and she’s packed it up, and she’s putting it away in the freezer. It’s kind of a little story that happens sort of behind Steve’s anecdotes, and that’s super fun to draw.

You obviously have insight into Steve Martin outside of his onscreen persona. What surprised you about him?

He’s a super nice guy. And he’s just very easygoing. He knows more about art than I had anticipated. He’s got very good instincts about art — he will look at some of my drawings and he’ll say, this one reminds him of a Homer, or this one reminds him of an early John Sloan etching. He’s just really, really great to work with, because he really appreciates it. He appreciates the drawing — that I wasn’t expecting, I really wasn’t.

You actually come from a family of artists yourself.

Yeah, my parents met in art school in the late ’50s. I always joke that growing up, if you couldn’t tell the difference between a Braque and a Picasso, you were beaten with a pussy willow branch that my dad would grab from the backyard. [laughs] My sister’s a painter, and my two cousins are illustrators, my brother Charlie is a great wildlife painter, and my brother John, who’s an educator, he can draw, too. I guess it’s genetic.

The house was filled with art, art books everywhere. So you couldn’t escape it, really. I’ve super fond memories of going over to my uncle’s house when I was 7, 8, 9, 13, 14, and my two cousins, Jim Bliss and Phil Bliss, they’re terrific illustrators — I would go over and look at their desks and just be blown away at what they were working on, and they were successful! Super inspiring for me, just awesome … I can still think back on how excited I was — it was just a ranch house, but you’d wind around these little corners and in the back of the house was this big studio with these big drawing boards set up and lights, and there was always a beautiful illustration just laid out on the table, and me and my older brother Charlie would just be flipping out. And then that night we’d go home and just be completely inspired, and we would draw.

And it was also an escape from pretty heavy dysfunction. The ’70s were pretty messed up if you grew up in a lower middle class neighborhood in upstate New York. It was bleak … There were moments that were good, but you know, it was just a different time. Kids were just mean to each other, man. They were just not nice. There was a fight after school every day, and it was just textbook, like in the movies. They would just cheer them on, like, “Fight! Fight! Fight!” I used to see fights constantly. I got punched in the arm from my brother’s friends, you know, every day … Looking back I can laugh about it, but at the time it sucked. You know, you constantly live in fear.

So the idea that I’m getting at, I guess, is that art was an escape, and it was a way to control your life when everything else going on in your life is out of control. You can sit down at your desk and have control over this thing, this white piece of paper, and make up your own kind of destiny. That was a huge thing for me.

I’ve been seeing you over the last couple of weeks promoting the book on various shows, like when you appeared with Steve on “The View.” It seems so non-cartoonist like! What has this whole experience been like for you?

Well, we did a Town Hall show [in New York City], which was just awesome, with Nathan Lane moderating. Me, Steve, and Nathan Lane — God, that was funny. Those guys are so good and quick, and Steve played the banjo at the end. So that kind of thing is just great. That’s just fun. I’ve spent enough time with Steve and his wife, and I’m pretty comfortable around them, you know. Part of that is working for the New Yorker — when you work for the New Yorker you end up at parties with David Byrne and Kevin Kline, and you know, you act like an idiot once or twice and you learn not to do it again.

But “The View,” man, that was crazy. I’m just glad I was sober. The thing about “The View” is that when you come out there and sit down, I saw beyond the audience. I saw the audience, all masked, I saw the walls. Then, beyond that, I saw New York City, then beyond that I saw the communication of everybody tuned into “The View,” and I imagined in my mind, how strange this whole setup, this thing that we’re doing right now is! I guess I was very, very present in that moment. I was in awe of the moment — I thought, this is just mind blowing to me. I don’t know how I made it through it.

Well, Steve actually makes it really easy for me, because he makes me laugh. And if you watch that clip I actually exclaim, “I’m really nervous!” And Steve says, “Why are you nervous?” “You know, because this is live.” And Steve’s like, “This is LIVE?” … He’s just a pro, he’s done it a gazillion times. So he made it really easy for me.

For the full conversation with Harry Bliss, including more on his New Yorker career, his drawing techniques, his favorite all-time cartoons, and the stories behind “Number One is Walking,” listen to the episode of Strip Search: The Comic Strip Podcast below.

Stay up-to-date on the Book Club

Catch up on the latest Boston.com Book Club pick and join the virtual author discussions.