Arts

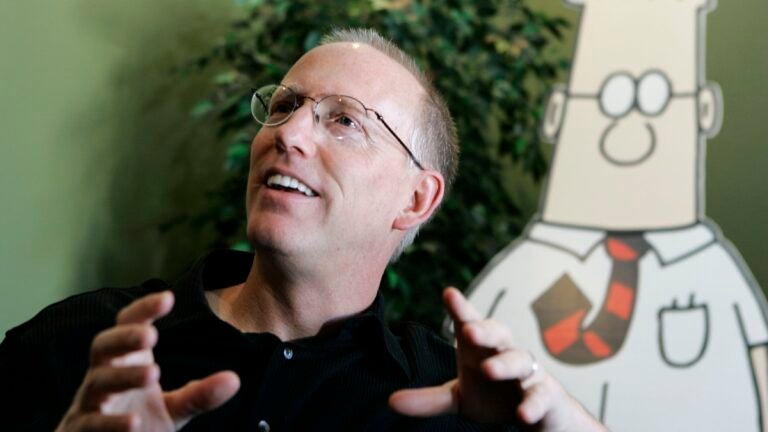

“I shook the box intentionally,” Scott Adams told the Washington Post about the comments that prompted newspapers to drop his comic strip.

Scott Adams sat for his regular YouTube show last month with a plan to stir a hornet’s nest. What he says he didn’t anticipate was how badly he would get stung.

“I shook the box intentionally. I did not realize how hard I shook it,” he told The Washington Post via text.

On his Feb. 22 episode of “Real Coffee With Scott Adams,” the creator of the comic strip “Dilbert” decided to riff on a much-criticized Rasmussen poll and promote a type of segregation. He declared that Black Americans are part of a “hate group” and urged White people to “get the hell away from Black people.”

By the following weekend, his syndicate and publishers were getting far away from him, severing business ties and halting future projects. So were hundreds of newspapers, including The Post and The Boston Globe, that dropped “Dilbert” from their pages.

Adams tells The Post that his remarks that day were intended to be hyperbole, while also contending that he was responding to a larger sociopolitical narrative. He does not apologize for what he said in the episode – viewed more than 360,000 times – though he asserts that he disavows racism. Meanwhile, on a follow-up “Real Coffee” podcast, he called both White people and the press “hate groups.”

It’s unknown just how many clients “Dilbert” still has. Yet on March 13, Adams plans to launch “Dilbert Reborn” on his subscription site, Locals. The first strips will feature his character Ratbert as a “context removing editor” at a media outlet that spoofs newspapers like The Post, he said via text. (He declined a request for an extended interview.)

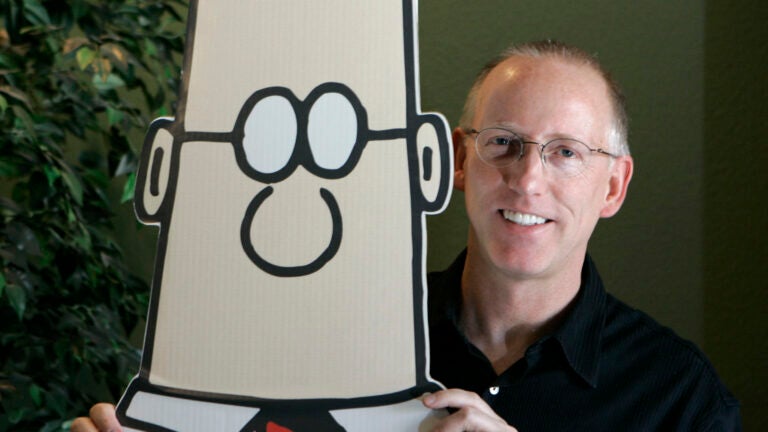

The comic about the lives of beleaguered cubicle-culture drones was once an omnipresent source of humor in American culture, capturing white-collar cynicism and malaise before “Office Space” and “The Office,” even entering Adams’s satiric corporate-incompetence concept “the Dilbert Principle” into national conversation. The strip appeared in more than 2,000 papers at its peak – rarefied air then populated by “Peanuts” and “Garfield” – and sparked a series of best-selling business books, a short-lived TV show and lines of merchandise.

Now, “Dilbert” has been banished from its longtime channels of mainstream distribution, resulting in an 80 percent loss of income, Adams said. For close observers, the story of Adams, 65, has taken a startling turn – though in a manner that had been foreshadowed in recent years as the cartoonist rebranded himself as a provocateur, routinely making headlines for his polarizing views on politics, race and other aspects of identity.

Said James Toler, who helped sell “Dilbert” to many newspapers three decades ago as a representative for its syndicate, United Media, “I am surprised at the speed with which Scott’s fall from grace occurred.”

‘Dilbert’ goes from comic to cultural smash

In United’s Madison Avenue offices, Sarah Gillespie spotted something unique while discovering “Dilbert” in the late ’80s while serving as director of comic art. “The take on office life was new and on target and insightful,” Gillespie said recently by email. “I looked first for humor and only secondarily for art, which with ‘Dilbert’ was a good thing, as the art is universally acknowledged to be … not great.”

Adams had grown up as a fan of “Peanuts,” he told The Post, and was thrilled to hang out with creator Charles M. Schulz after joining United.

By 1990, United had signed several future stars, including Adams; Robb Armstrong, creator of “JumpStart,” one of the most widely syndicated strips ever by an African American artist; and Lincoln Peirce, creator of “Big Nate.”

“It was absolutely electric,” Armstrong said of that time, noting that new cartoonists “were ecstatic about the opportunity in front of us.”

Peirce said: “It was clear to me that they thought ‘Dilbert’ was going to be their next game changer – something that could eventually join ‘Garfield’ and ‘Peanuts’ in the pantheon of heavy hitters. The funny thing was, some of the sales staff seemed to really get ‘Dilbert,’ and others didn’t.”

The young cartoonists attended a Washington sales conference together. Armstrong – who once considered Adams a friend – remembered the “Dilbert” creator as an unassuming presence then who embraced self-help books and courses. “He was chatting us up about a Dale Carnegie class he was taking,” Armstrong recalled by text. “He said it was helping him tremendously and that he was becoming comfortable speaking in front of people.”

“Funny to ponder that now,” he said. “Actually, it’s not funny now.” (Adams would later effusively blurb a 2016 book by Armstrong, who was heartbroken last week upon hearing Adams’s racist rant.)

Amy Lago, the main editor of “Dilbert” at United from 1995 to 2002, recalled that when each new batch arrived by mail from Adams, laughter gradually rippled from the administrative assistants toward the inner offices of executives. “Translating that laughter into sales was not easy,” though, said Lago, now a cartoon executive at Counterpoint Media. (She and Toler have worked at The Washington Post Writers Group.) “The consensus among the sales representatives and even some executives was decidedly against the strip.”

“Scott Adams was on the phone bemoaning the low numbers to me” not long after the launch, Lago said. “When I told him that ‘Peanuts’ started with one-tenth of that number, he was surprised.”

One major objection to “Dilbert,” Toler recalled, was that newspaper editors felt the title character looked a bit like the recently introduced Bart Simpson. Another was that newspaper managers objected to Scott’s poking fun at management.

“However, as the same managers walked through their buildings, it became clear that ‘Dilbert’ was a favorite of employees in all departments, as ‘Dilbert’ strips were taped to the walls of cubicles throughout the buildings,” Toler said. By mocking business through starkly unadorned panels, Adams had a satiric and visual niche – a combination that Toler found appealing.

By the mid-’90s, two developments proved crucial.

Adams became the first prominent cartoonist to include his email address in the strip, Lago said. Readers responded in droves, encouraging the workplace storylines in “Dilbert” and offering him ideas. “This practice gave Adams and the syndicate something special: direct commentary from readers,” Lago said. Soon, the syndicate reps were traveling with reams of “Dilbert” fan emails in their cases – an effective prop for sales calls.

Then, in 1995, Gary Larson and Bill Watterson ended their hugely popular strips, “The Far Side” and “Calvin and Hobbes,” respectively. United Media sales reps worked the phones. “I don’t remember the actual numbers,” Lago said, “but I’d guess that the ‘Dilbert’ sales list doubled.”

The strip sales became a springboard that boosted “Dilbert” licensing and merchandise, as well as how-to publishing. Adams’s first two hardcover business books sold more than 2 million copies, according to HarperCollins. Adams’s bespectacled titular character was soon on-screen in office supply commercials as well as a United Paramount Network animated series, with Daniel Stern voicing Dilbert.

Adams also liked to push the envelope of traditional taste in family newspapers, including a strip about naming products that had the punchline “Uranus Hertz.” Lago said she took the unusual step of providing substitute strips for newspaper clients who found the original strips objectionable.

By 1998, a formally attired Adams was in a Pasadena, Calif., ballroom at the top of the heap, picking up the National Cartoonists Society’s esteemed Reuben Award as outstanding cartoonist.

“At its height, ‘Dilbert’ was fabulous,” said Mike Peterson, columnist for the industry blog the Daily Cartoonist. “It was a real poke in the eye, and we needed it.”

One devoted reader at the time was future cartoonist Mattie Lubchansky (“Boys Weekend”), who became “weirdly a huge fan” as an adolescent. “I thought to myself, ‘This is what adult life would be like!’” the artist said.

Lubchansky, though, was among those who noticed distinct changes in “Dilbert” at least a decade ago, even drawing a 2016 comic titled “The Fall of Dilbert.” “His comics had strangely become more about his own petty grievances and were even sympathetic to the boss,” they said, noting that Adams began posting selfies of his abs on Twitter in an attempt to deflect debate.

“He’s been acting stranger and stranger in public for the last 10 years – and even if you read his comic collections from the ’90s with his commentary, there’s all sorts of anti-‘PC’ rambling that was always there,” Lubchansky said.

“I think society has just stopped lionizing this kind of guy.”

Adams falls out of favor

Adams’s polarizing opinions peeked into public view in a blog post from 2006 in which he questioned the death toll of the Holocaust to illustrate his belief that news stories lack context. In 2021, he turned to Twitter to defend actress Gina Carano, who was ousted from “The Mandalorian” for comparing being a Republican to being Jewish during the Holocaust: “Fired for making a Hitler analogy? Wouldn’t that employment standard make all of us unemployed?” Adams wrote.

Some of his comments were viewed as sexist. In a later-deleted 2011 blog post, he angered readers with a men’s rights tirade, in which he argued that it’s not worth trying to appease women for the same reason it’s not worth rationalizing with children and mentally disabled people. “It’s just easier this way for everyone,” he wrote. “It’s the path of least resistance. You save your energy for more important battles.” Adams implied in a later blog post that he was amused by the uproar his remarks caused, but he ultimately apologized.

In late 2015, in stark contrast to seasoned pollsters, Adams said he was almost certain that Donald Trump would be the Republican presidential nominee, and later president, because of the New York businessman’s “persuasive talent.” He partly based his claim on his own training as a hypnotist.

Adams said in 2016 that he didn’t vote and didn’t belong to a political party, but since then, he’s sent mixed messages about his political leanings, blurring the lines between his genuine and satirical statements on Twitter and YouTube. On a recent “Real Coffee” episode, Adams said he had supported Barack Obama and Bill Clinton because “I liked having a smart president.”

Much of his Twitter audience felt he was using tragedy for his own personal gain when, on the day of the 2019 Gilroy Garlic Festival shooting, Adams asked witnesses to join WhenHub, a video app he created as a peer-to-peer “newsgathering tool.”

Adams didn’t make major waves with a February 2021 comic that poked fun at those who received a coronavirus vaccine, but he did ruffle feathers when he espoused debunked claims that people who weren’t vaccinated fared better than those who were, in a video shared by the “Just Think” podcast.

In the 2020s, his political statements also started to focus more on race. At the beginning of 2022, he tweeted that he was “going to self-identify as a Black woman until Biden picks his Supreme Court nominee,” which the president had vowed would be a Black woman. And in June 2020, Adams tweeted that when the “Dilbert” TV show ended in 2000 after just two seasons, it was “the third job I lost for being white.”

(His claim has been widely disputed. When the show was nixed, Adams told the GroundReport it was because of lower viewership and time slot changes. When he was laid off from now-defunct telephone company Pacific Bell in 1995, he told reporters it was because of budget constraints. And when he was laid off from Crocker National Bank in 1986, he was one of thousands of other workers who were also let go.)

“Dilbert” comics also took on Adams’s views on race and identity, through “Dave the Black Engineer,” a character who was introduced in a May 2022 strip. Although Dave is hired to abide by management’s request for more diversity, he immediately declares that he identifies as White to “prank” the boss. In a strip published days later, the boss thanks team members for identifying as Black to meet “diversity targets.”

In September, Dave was asked to “identify as gay” to boost the company’s environmental, social and governance (ESG) rating after being given a promotion. And in October, a series of strips show co-workers Dave and Tina being considered for a job to “meet DEI goals” (diversity, equity and inclusion) despite knowing they were unqualified.

In addressing the context for his recent racist rant, Adams texted The Post, “The real story is the narrative poisoning that is coming from ESG, CRT, DEI,” referring also to critical race theory.

Adams has anticipated multiple times that his tweets or live streams would get him “canceled.” And finally, in his stream on Feb. 22, his statements became too inflammatory to ignore. He reacted to a Rasmussen poll that asked Americans whether they agreed or disagreed with the statement, “It’s okay to be White.” Adams said Black Americans were part of a “hate group” based on the poll results, which revealed that about 26 percent of Black people strongly or somewhat disagreed with the statement and an additional 21 percent weren’t sure. But the poll has been called misleading because the slogan is one that white supremacists popularized in a 2017 trolling campaign. Respondents who disagreed or weren’t sure about the statement might have recognized the phrase from its white-nationalist context or might have been put off by the odd phrasing.

“As you know, I’ve been identifying as Black for a while, years now, because I like to be on the winning team,” Adams said in his YouTube live-stream show. “But as of today, I’m going to re-identify as White, because I don’t want to be a member of a hate group.”

“I would say, based on the current way things are going, the best advice I would give to White people is to get the hell away from Black people … because there is no fixing this,” he added.

Adams’s syndicate and publisher Andrews McMeel Universal said his rant was not in line with the company’s values. Another Adams publisher announced it would not publish his scheduled book, “Reframe Your Brain.”

Adams acknowledges that while he intended the remarks to break through beyond his “bubble,” which includes about 135,000 YouTube subscribers, he was caught off-guard by the extent and the impact. He told The Post he was surprised that “the cancel-culture people” were able to get to the “choke points” that were his various publishers.

“I didn’t know Scott on a personal level, but what he has become is so very different from the man I thought I knew,” said Gillespie, who discovered him at United. “I am appalled and saddened.”

Over the sudden loss of so much income, Adams said, “Politics is the reason for the cancellations.” But he seems undeterred. Famous figures such as Elon Musk and Turning Point USA founder Charlie Kirk have come to his defense.

“Only the dying leftist Fake News industry canceled me (for out-of-context news of course),” Adams tweeted Thursday. “Social media and banking unaffected. Personal life improved. Never been more popular in my life. Zero pushback in person. Black and White conservatives solidly supporting me.”

The political polarization of a once-uncontentious comic strip points to an issue much bigger than Adams, said Ruben Bolling, the Herblock Prize-winning creator of the syndicated comic “Tom the Dancing Bug.”

“So many in the MAGA-sphere have been emboldened to drop their coded racism and make hateful statements that are increasingly overt,” said Bolling, while nodding to Rep. Lauren Boebert, a far-right Republican congresswoman from Colorado (whose representatives did not immediately respond to requests for comment). “It’s not just Dilbert. It’s Boebert.”

Meanwhile, on his Saturday show, Adams cited a favorite quote as he seeks his commercial outlook going forward: “In chaos, there is opportunity.”