An Atlantic storm crashed over the eastern strip of Norton Point Beach in the last days of 2022, inundating Wasque wetlands and disconnecting Chappaquiddick once again. The breach created an old, yet new island to ring in 2023, a fitting start for a year in which many longstanding issues resurfaced.

“We’ve seen the natural cycle repeat itself. And it will happen again,” said Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute scientist Steve Elgar of the breach, which was last opened in 2015.

His words were prophetic. In the final days of the year, another Norton Point breach opened to the sea, nature providing a bookend to a year of tension on many fronts — the housing crisis deepened, debate over the use of artificial turf at the regional high school grew heated and water quality declined. Lawsuits were filed and appeals were made.

Through it all, Vineyarders continued to seek answers to issues with no easy solutions. And in times of loss and hardship, Islanders united in solidarity, as they always do.

“The storms come, and the sand moves around,” Mr. Elgar said of the breach. But it holds true in a broader sense, too.

The year began, as it often does, with a birth.

Sol Cove Fischer arrived at 3:45 p.m., born at home on New Year’s Day to parents Lila Fischer and Nic Turner, weighing in at 8 pounds and 2 ounces.

The very same day, at the crack of dawn, dozens of birders fanned out across the Island for the annual Christmas Bird Count, looking to tally as many species as they could in a 24-hour period. Greater yellowlegs were plentiful, but there was not a single pied-billed grebe to be found.

“Here’s to a Christmas Bird Count in sweaters,” toasted Gazette bird columnist Robert Culbert, acknowledging the unseasonable warmth with a jovial remark, highlighting the ever-changing environmental conditions around the world and on-Island.

The first newborn baby and the annual avian tally were markers of tradition, yet they contrasted with a community that often seemed strained to the point of fracture.

New Year’s Day baby Sol Cove Fischer Turner, with parents Nic Turner and Lila Fischer and big sister Zinnia.

— Ray Ewing

Nowhere was this clearer than in the ongoing battle over whether to use artificial turf on the regional high school playing field, which came to dominate town meeting season. The three up-Island towns voted not to fund the high school budget in order to protest the school committee’s spending on litigation with the Oak Bluffs planning board over the latter’s denial of the artificial turf project.

“We’re setting an unbelievably bad example for our children by suing ourselves. It’s the most idiotic thing I’ve ever heard of,” said West Tisbury resident Kate DeVane, at town meeting.

As the year ended, the stalemate over turf continued, with the Oak Bluffs planning board voting 2-1 to appeal a land court ruling in the school committee’s favor.

Consensus was hard to reach on several other issues around the Island.

In West Tisbury, a long-awaited renovation to the Howes House was paused after pushback from the historic district commission and disagreement from other towns that use the Up-Island Council on Aging.

Down-Island, the Oak Bluffs select board reckoned with town identity as it cracked down on doughnut-line noise and changed regulations for local bars, adopting an earlier last call.

Oak Bluffs residents, meanwhile, quickly defeated a plan put forward by Harbor Homes for a new homeless shelter in town, even as the number of homeless on the Island continued to grow. When the current shelter opened for the season in late 2023, it had to carve out additional space to meet the demand.

In Tisbury, local government officials were under pressure as questions were raised about town organization, shellfish policies and rapidly-deteriorating conditions at facilities, in particular at town hall.

“The actual building needs to go away,” said Tisbury employee Amy Upton. “It’s garbage. There’s nothing to be done.”

Even in serene Chilmark, the thwack of pickleball paddles raised hackles, as officials reckoned with whether to ban construction of pickleball courts.

“If you have a pickleball paddle in your car, are you subject to search and seizure?” mused planning board member Cathy Thompson, as the board looked into the ban.

Changing town character also came to the fore in Edgartown. Unpermitted demolitions and proposed changes to the historic Mayhew Parsonage raised questions about how best to preserve the town’s historic heritage, while parties put on by whiskey company Uncle Nearest’s corporate-owned home highlighted a loophole in town zoning bylaws.

And, as ever, the Steamship Authority was a lightning rod for controversy. The company’s new website was further delayed, costs to outfit new freight ferry vessels rose and an incident with the M/V Sankaty breaking loose from its moorings and the subsequent internal investigation that came to light had the Steamship’s governing board questioning organizational leadership.

“All of [this] points to a serious fall down in the senior management of the Steamship Authority,” said Vineyard Steamship representative Jim Malkin, of the Sankaty affair.

Even the animals seemed controversial this year, with emotions running high over goats and coyotes.

“If you don’t believe [coyotes] are here then you are mistaken,” said coyote expert Dan Proulx, to a packed and rather anxious room at the Agricultural Hall in February, before urging a message of unity.

“You guys are an Island,” he said. “Work as a team.”

Environmental concerns also percolated throughout the year. Toxic cyanobacterial blooms afflicted the great ponds throughout the summer, fed by nitrogen pollution from thousands of septic systems. Earlier in the year, it looked like the state might take regulatory action on the nitrogen problem, before pulling the Island out of a plan to impose sweeping septic regulations at the 11th hour.

The Trustees of Reservations faced repeated rebukes as the organization’s approach to conservation came under scrutiny. After giving up management of Norton Point Beach late last year, and bringing on a new chief executive officer in early 2023, the battle over whether to allow vehicles to drive on Chappaquiddick beaches raged for much of the year, without a clear resolution.

Also on Chappy, a long battle against erosion was lost to Mother Nature, following the first Norton Point breach. Teetering on the brink, the Chappaquiddick summer home owned by Sue and Jerry Wacks was demolished in February.

“Here we are in 2023 and the rate of sea level rise has increased. Houses have been lost to the sea and will continue to be lost to the sea,” wrote retired Trustees superintendent Chris Kennedy. “And I still wonder: when will we accept that sea level rise is happening? And what is Plan B?”

Forests, too, came under stress, with beech and pine trees threatened by pests, and worries of forest fires looming large.

Still, it was not all bad news for Island ecosystems.

Bats, bees and shorebirds all showed signs of recovery, while the Martha’s Vineyard Land Bank succeeded in major conservation purchases, acquiring 4.5 acres of land on the shore of Ice House Pond in West Tisbury, teaming up with Sheriff’s Meadow Foundation to conserve the historic, 166-acre Pimpneymouse Farm on Chappaquiddick and preserving a swath of Flat Point Farm in West Tisbury with a 100-year lease.

On the waterfront, the Martha’s Vineyard Striped Bass and Bluefish Derby completed its 78th year, once again without striped bass, but with a strong showing of triple crown winners — those who weigh in bluefish, bonito and false albacore. A multitude of huge bluefish crossed the scales in the final week.

Two derby fixtures were inducted into the fishing event’s hall of fame this year, Paul Shultz and Joe El-Deiry, who spoke tearfully at the award ceremony.

“Fishing isn’t solely about the catch,” Mr. El-Deiry said. “It’s about fostering connections . . . nurturing a sense of community.”

In March, Islanders got moving, literally, to confront the affordable housing crisis. After approving a home-rule petition at town meeting in 2022 to form an Islandwide housing bank only to see the legislation stall at the state house, hundreds of Vineyarders boarded a 7 a.m. ferry on March 23 en-route to Boston to lobby for the passage of the Housing Bank bill.

“I’ve seen a little over 57 per cent of my friends leave the Island because of housing,” said Graysen Kirk, then a senior at the Martha’s Vineyard Public Charter School, a sentiment echoed by many others that day, and in articles throughout the year.

The issue, and efforts to combat it, continued to emerge on multiple fronts.

Edgartown, Oak Bluffs and Aquinnah all moved forward on town-sponsored affordable housing developments, while the Seastreak ferry extended its summer New Bedford service to year-round, catering to a growing commuter population.

The end of the year saw a number of private affordable housing development proposals, each with mixed reviews. Vineyard planners, meanwhile, began to look to neighboring resort communities for solutions.

“They’re about five years ahead of us,” Edgartown planning board chair Lucy Morrison said of Nantucket. “Their situation is much more dire, but because of that there’s been more action.”

For the Martha’s Vineyard Commission, it was an active year, and one of mixed legal results.

Major projects were approved, often after lengthy debate, including a mixed-use development at the old Stone Bank in Vineyard Haven, a new nonprofit event space called Stillpoint in West Tisbury, a marina expansion on the Lagoon, a new location for Island Grown Initiative’s food pantry and a large addition to the YMCA.

In a closely-watched case that tested the limits of the MVC’s authority, a Superior Court judge upheld the commission’s denial of the Meetinghouse Way subdivision on the outskirts of Edgartown. The decision, however, cited flaws in the commission’s reasoning, and two other legal opinions issued the same week in April tempered the victory. In one case, the MVC was found to have violated the open meeting law and in another to have exceeded its authority by rejecting the design of an Island Elderly Housing building.

“It’s been a week of hard truths for the Martha’s Vineyard Commission,” read a Gazette editorial. “With the Island now facing very real limits on growth, the commission needs to focus on the big picture and ensure that its decisions are clearly justified and thoroughly articulated.”

At sea, Vineyard Wind began construction on the nation’s first commercial-scale offshore wind project in waters south of the Island, even as other windfarms planned for the area struggled financially.

“We can finally say it — as of today, there is ‘steel in the water,’” said Klaus Moeller, chief executive officer of Vineyard Wind, in an early June press release.

By the end of the year, the first five turbines were complete — only 57 more to go.

Back on dry land, smaller development projects proceeded as well. The Edgartown Stop & Shop completed its new wing, and forests were cleared for Navigator Homes and a new nursery for Donaroma’s.

Among the most anticipated was the completed renovation of the ArtCliff Diner, which reopened in September after a nearly two-year hiatus to a line of hungry regulars.

“It’s sweet, you know, to see people in their 70s and 80s come in [and] they tear up when they see it,” said chef-owner Gina Stanley on reopening day.

In June, a replica of the slave ship Amistad sailed into Vineyard Haven harbor, part of the Island’s ever-expanding Juneteenth celebrations.

Throughout the summer, several nonprofit organizations enjoyed major milestones. Polly Hill Arboretum celebrated its 25th anniversary while the Martha’s Vineyard Museum turned 100 years young. In Aquinnah, a native-run domestic violence program created in 2020 called Kinship Heals raised $2 million to acquire a 7.8-acre plot to construct a food pantry, domestic violence shelter and ceremonial site for members of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah).

“I can’t even begin to describe… the outpouring of love and support that was given,” said director Jennifer Randolph. “It was really amazing.”

A few months later, a new nonprofit called Native Land Conservancy purchased the Aquinnah Shop, with plans to sell the business to an Aquinnah group, thus putting the cliffside restaurant back in Wampanoag hands.

Also representing Aquinnah, select board member and community leader Juli Vanderhoop won the Creative Living award.

“Bringing people home matters,” Ms. Vanderhoop said of her town, in an interview with the Gazette. “This is the place where we heal.”

MV Youth continued to put money where it matters, pledging $1 million at year’s end to the Boys and Girls Club for its new campus, while also awarding $946,000 in college and workforce scholarships to 16 high school seniors.

Also in a giving mood, the Martha’s Vineyard Bank’s charitable foundation gave away $1.1 million in community grants, including a $1 million grant to Island Grown Initiative to help relocate the food pantry’s distribution center.

2023 was a time for grief as much as for celebration, as the Island said goodbye to many whose lives touched the community in a variety of ways.

Edith Blake, a giant of Edgartown society who chronicled the making of Jaws, died at 97. Island potter Tom Thatcher died at 96.

Fred Mascolo, 65, better known as Trader Fred, personified an old retail ethos, while Lori Robinson Fisher, 67, made her mark with the popular Islanders Talk Facebook page. Tony Rezendes, 80, owned the Square Rigger restaurant.

Leonard Butler, 74, spearheaded the Gay Head Lighthouse move; Charles J. Ogletree Jr., 70, was a leading constitutional scholar and activist; and Robert Solow, 99, split his time between MIT and Chilmark, winning a Nobel Prize in economics along the way.

Clifton Athearn, 100, helped to liberate Buchenwald and was the last person to have seen a live heath hen. James Reston Jr., 82, was a writer and previous co-owner of the Vineyard Gazette.

Shannon Gregory Carbon, 53, was a beloved teacher at the Tisbury School.

Tafari Campbell, 45, private chef to the Obama family, drowned in a paddleboarding incident in the Edgartown Great Pond.

And the deaths this fall of teenagers Yossi Monahan and Waylon Sauer shook the Island community.

“The Agricultural Hall . . . did not empty out until deep into the evening Sunday,” wrote a Gazette editorial, on the memorial following Waylon’s death. “Islanders did what they do best, they showed up and held each other, and they did not let go.”

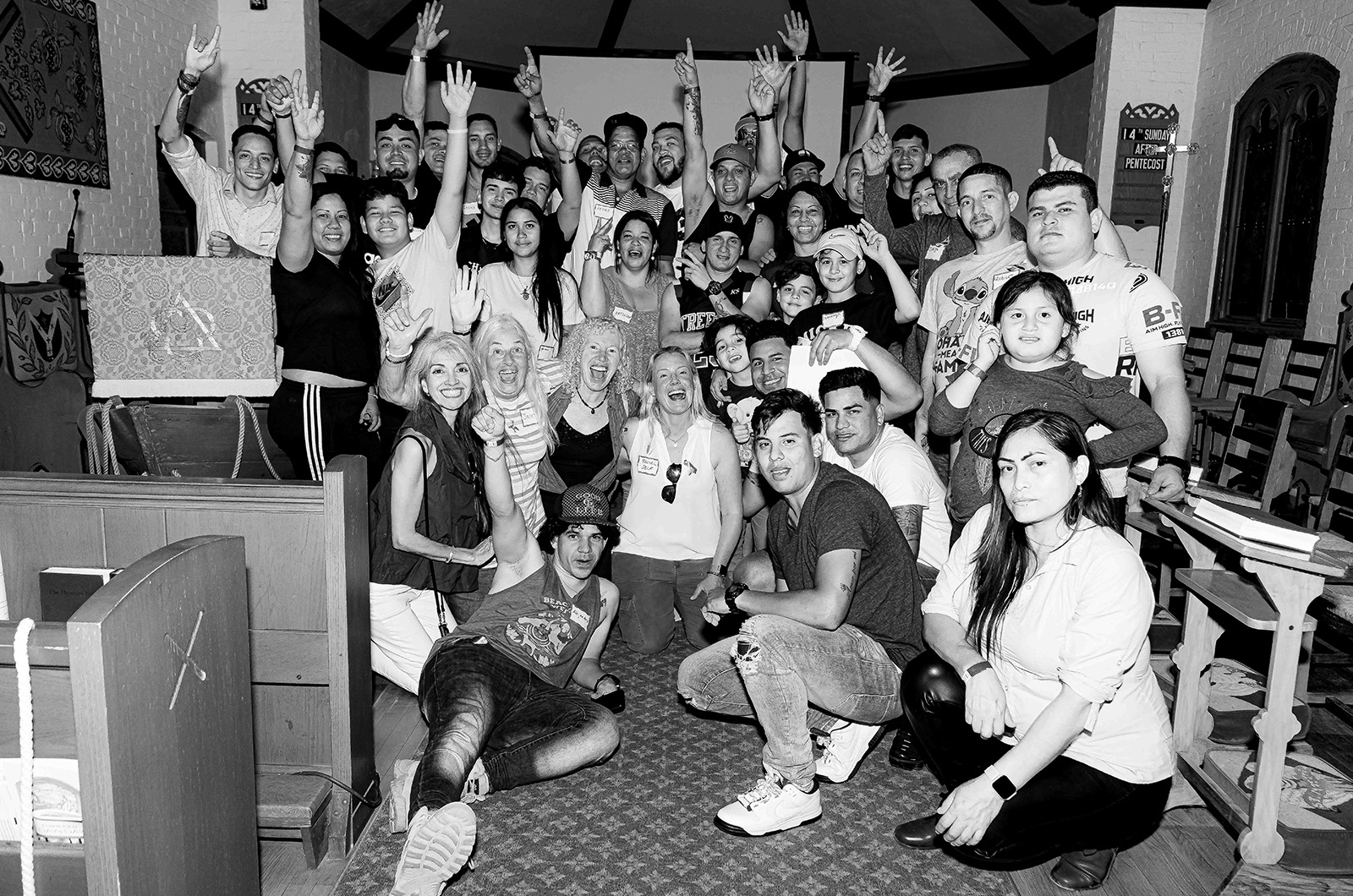

Migrant reunion took place in September, with 62 people returning to the Island to celebrate together.

— Lucy Dahl

Retirement stories also filled the pages of the Gazette, including longtime town health agents Matt Poole and Maura Valley.

Warren Doty ended his 24-year run on the Chilmark select board, and Brendan O’Neill passed the torch as director of the Vineyard Conservation Society to Samantha Look. Longtime Chilmark school principal Susan Stevens announced her impending retirement at the end of the coming school year.

In Menemsha, Virginia Jones closed up her used bookshop, announcing plans to “sit in a comfortable chair with a nice cup of tea and my knitting, and a good book.”

Amidst the goodbyes, there was also a reunion, when most of the Venezuelan migrants sent to Martha’s Vineyard by Gov. Ron DeSantis reunited on-Island this September. For four of them, it was a short trip, after having permanently relocated to the Vineyard.

“We’re lucky to be alive….There were people who didn’t make it. Many people died,” recalled one new resident, Daniel, of the arduous journey north that ended unexpectedly on the Island,

“We just have to keep moving forward,” he said.

On a blustery day at the start of the year, Island naturalist David Foster took a stroll along Stonewall Beach. He was there for a log, the 10,000-year-old remnant of a sturdy white pine jutting from the cliff, revealed by years of erosion.

It was an encounter with a vast timescale and an opportunity to reflect on the nature of change.

“The big lesson from studying the past is, yes, change is constant, but the change we are generating these days is at such an extraordinary pace relative to the past,” Mr. Foster said, a point made all the more prescient when, at the end of 2023, a prolonged windstorm reshaped the bluffs and beaches along much of the Island’s south shore.

But even through so much change, for many it is what remains the same that binds them to the Island.

“This place still attracts the same people it attracted when I came here 57 years ago,” said Richard (Dick) Fligor, 87, who after years as an Edgartown retail mainstay, has shifted to poetry, releasing his second volume this year.

Despite all the changes he has seen, to the Island and the people on it, the Vineyard community still remains something special.

“That’s what inspired me to be a Vineyarder,” he said. “Be artistic, be learned, be family, be whole.”

Even perched on shifting sands, it’s something the Vineyard can always count on.