Arts

“He was a Black playwright who spoke to the values of the urban experience…”

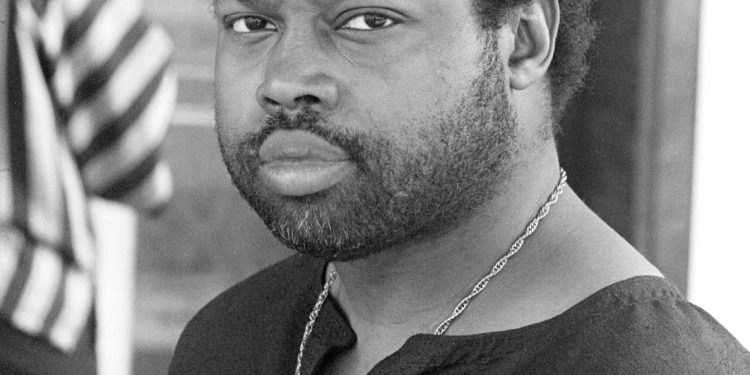

Ed Bullins, who was among the most significant Black playwrights of the 20th century and a leading voice in the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and ’70s, died on Saturday at his home in Roxbury. He was 86.

His wife, Marva Sparks, said the cause was complications of dementia.

Over a 55-year career in which he produced nearly 100 plays, Bullins sought to reflect the Black urban experience unmitigated by the expectations of traditional theater. Most of his work appeared in Black theaters in Harlem and Oakland, California, and perhaps for that reason he never reached the heights of acclaim that greeted peers like August Wilson, whose plays appeared on Broadway and were adapted for the screen (and who often credited Bullins as an influence).

That was fine with Bullins. He often said he wrote not for white or middle-class audiences, but for the strivers, hustlers and quiet sufferers whose struggles he sought to capture in searing works like “In the Wine Time” (1968) and “The Taking of Miss Janie” (1975).

“He was able to get the grassroots to come to his plays,” writer Ishmael Reed said in an interview. “He was a Black playwright who spoke to the values of the urban experience. Some of those people had probably never seen a play before.”

Although Bullins was a careful student of white playwrights like Arthur Miller and Eugene O’Neill, he rejected many of their conventions, pursuing a loose, rapid style that drew equally on avant-garde jazz and television — two forms that he felt put him closer to the register of his intended audiences.

He won three Obie Awards and two Guggenheim grants, and in 1975 the New York Drama Critics’ Circle named “The Taking of Miss Janie” the best American play of that year.

Not everyone was enamored of his work. Some critics, including some in the Black press, believed he focused too heavily on the violence and criminality he saw in working-class Black life, and reflected it too brutally — “The Taking of Miss Janie,” for instance, opens and closes with a rape scene.

But most critics, especially in the establishment, came to respect Bullins as an artist who was both passionately true to his source material and nuanced enough in his vision to avoid becoming doctrinaire.

“He tackled subjects that on the surface were very specific to the Black experience,” playwright Richard Wesley said in an interview. “But Ed was also very much committed to showing the humanity of his characters, and in doing that he became accessible to audiences beyond the Black community.”

Edward Artie Bullins was born on July 7, 1935, in Philadelphia and grew up on the city’s North Side. His father, Edward Bullins, left home when Ed was still a small child, and he was raised by his mother, Bertha Marie (Queen) Bullins, who worked for the city government.

Although he did well in school, he gravitated toward the North Side’s rough street life. He joined a gang, lost two front teeth in one fight and was stabbed in the heart during another.

He dropped out of school in 1952 and joined the Navy. He served most of the next three years as an ensign aboard the aircraft carrier USS Midway, where he won a lightweight boxing championship.

He returned to Philadelphia in 1955 and, three years later, moved to Los Angeles. He attended night school to earn a high school equivalency diploma, then attended Los Angeles City College, where he started a magazine, Citadel, and wrote short stories for it.

In 1962 he married the poet Pat Cooks. She accused him of threatening her with violence, and they divorced in 1966. (She later remarried and took the surname Parker.)

Bullins’ later marriage, to Trixie Bullins, ended in divorce. Along with his third wife, he is survived by his sons, Ronald and Sun Ra; his daughters, Diane Bullins, Patricia Oden and Catherine Room; and several grandchildren and great-grandchildren. Four other children, Ameena, Darlene, Donald and Eddie Jr., died before him.

Restless and unhappy with his work in Los Angeles, Bullins moved in 1964 to San Francisco, where he plugged into a growing community of Black writers. He also switched from writing prose to writing plays — in part, he said, because he was lazy, but also because he felt the theater gave him more direct access to the everyday Black experience.

His first play, “How Do You Do,” an absurdist one-act encounter between a middle-class Black couple and a working-class Black man, was produced in 1965, to favorable reviews. But he remained unsure of his decision to write plays until a few months later, when he saw a dual production of “The Dutchman” and “The Slave,” two plays by Amiri Baraka, then known as LeRoi Jones, a leading figure of the Black Arts Movement.

“I said to myself, I must be on the right track,” Bullins told The New Yorker in 1973. “I could see that an experienced playwright like Jones was dealing with these same qualities and conditions of Black life that moved me.”

The Black Arts Movement, then still primarily an East Coast phenomenon, was a loose affiliation of novelists, playwrights and poets whose work sought to reflect the modern Black experience on its own terms — written and produced by Black people in Black spaces for Black audiences.

Bullins had found his community, and, through it, his voice. He fell in with a circle of Bay Area writers, actors and activists, who began performing his work in bars and coffeehouses.

Among them was Eldridge Cleaver, who, after his release from prison in 1966, used some of the proceeds from his memoir “Soul on Ice” to found Black House, an arts and community center in San Francisco, with Bullins as its chief artist in residence.

Black House also became the city’s headquarters for the Black Panther Party, founded by Bobby Seale and Huey Newton. Bullins became the party’s minister of culture.

But his role in the Black Panthers was short-lived. The party, from his perspective at least, saw art solely as a weapon, and he chafed at Seale’s insistence that he create didactic, often explicitly Marxist plays. He also grew frustrated over the party’s interest in building a coalition with radical white allies, when what he sought was a movement wholly independent of white culture.

“I have no Messianic urge,” he told The New York Times in 1975. “Every other street corner has somebody telling you Christ or Mao is the answer. You can take any Ism you want and be saved by it. If you’re part of some movement and it fulfills you, that’s cool, but I like to look at it all.”

He left the party in late 1966, just before Black House shut down.

Bullins considered moving to Europe or South America, but he changed his mind when Robert Macbeth, the founder of the New Lafayette Theater in Harlem, invited him to be the artist in residence there.

He arrived in New York in 1967, and the next six years of work, mostly at the New Lafayette Theater, represented the peak of his career. The theater was a complete package: a 14-member acting troupe, 14 musicians, several playwrights and directors, and an affiliated art gallery, the Weusi Artist Collective, that produced sets.

Bullins also led workshops for aspiring playwrights, many of whom, like Wesley, went on to become significant voices among the next generation of Black theater artists.

A year after arriving, he completed “In the Wine Time,” his first full-length play and the first of a series he called his “Twentieth Century Cycle” — 20 plays that told the story of postwar urban life through a set of friends. In 1971 he won his first Obie, for “The Fabulous Miss Marie” and “In New England Winter.”

He left the New Lafayette Theater in 1973, shortly before it closed for lack of funding. His work in the 1970s appeared in the New Federal Theater, La MaMa Experimental Theater Club, the Public Theater and elsewhere.

In 1972 he got into a war of words with the Repertory Theater of Lincoln Center, which was putting on his play “The Duplex.” Although he had initially endorsed the production, he later said in an interview that “the original Black intentions” of the play had been “thwarted” and “its artistic integrity stomped on,” turning it into a “minstrel show.”

He traded attacks with the producer, Jules Irving, and the director, Gilbert Moses, in The New York Times and elsewhere, but in the end the play went on. It received mixed reviews.

That episode, fairly or not, gave Bullins a reputation for being hard to work with, one of the reasons he cited for returning to the West Coast in the 1980s. He continued to write plays, but he also produced work by others, including Reed, at his Bullins Memorial Theater in Oakland, named for his son Eddie Jr., who died in a car crash in 1978.

Bullins also returned to school. He received a bachelor’s degree in English from the San Francisco campus of Antioch University in 1989, and a master’s in fine arts in playwriting from San Francisco State University in 1994.

The next year he moved to Boston, where he became a professor in the theater department at Northeastern University. He retired in 2012.

By then he had long since changed his mind about his audience, in large part because he and others in the Black Arts Movement had succeeded in their mission to build a Black cultural canon.

“Of course Black writers can write for all audiences,” he told The New York Times in 1982. “My feeling is that the question of whether Black theater should appeal to whites was more valid a decade ago. Since then, Black theater has taken off in all directions.”

Newsletter Signup

Stay up to date on all the latest news from Boston.com