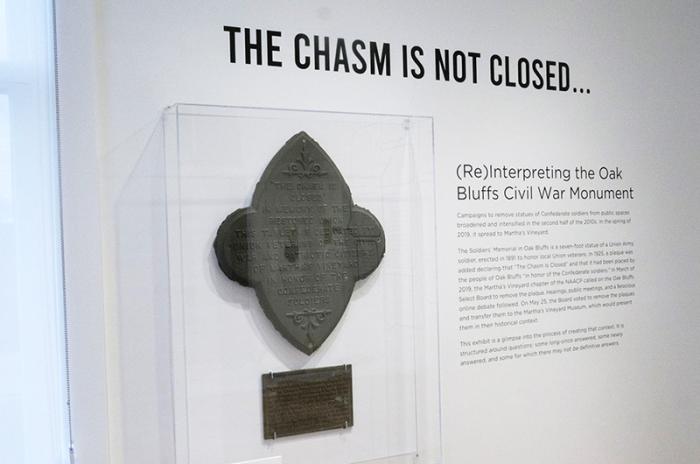

Nearly three years after a storm of public debate spurred Oak Bluffs selectmen to remove a pair of tributes to the Confederacy from the town’s 1891 monument to the Union side of the Civil War, the controversial plaques are back on display.

At the request of the Vineyard chapter of the NAACP, the two metal plates were donated to the Martha’s Vineyard Museum, where they are currently on view in a new exhibit titled The Chasm is Not Closed.

Curator Anna Barber said this is the museum’s first step toward creating a permanent exhibition centered on the plaques.

“We are still very much in the process of learning and collecting feedback,” Ms. Barber said in an interview. “We’re trying to figure out how do we fit this statue into its place in history, and how does that help us going forward?”

“This is first time we’ve ever done an exhibition where we’re saying, we’re learning,” she said.

The statue was put up in 1891 by Charles Strahan, a former Confederate soldier who relocated to the Vineyard and began publishing the Martha’s Vineyard Herald. Mr. Strahan had family members on both sides of the Civil War; the statue was created as a memorial to honor Union soldiers. Plaques honoring Confederate soldiers were added in 1925 and were meant to represent a reconciliation between the two sides of the war.

As late as 2001, when the monument was rededicated, the binary brother-against-brother Civil War narrative remained unchallenged.

In 2019, amid the nationwide Black Lives Matter movement, activists and Islanders began to question the plaques and debate their appropriateness. The NAACP became involved, and eventually the town decided to remove the plaques from the statue and donate them to the museum.

In addition to the plaques, the museum exhibit gathers artifacts and new scholarship to draw a fuller picture of Island life, both before and after the Civil War.

Proving that Martha’s Vineyard was no exception to the racism pervading American life, a printed ticket to a 1922 minstrel show by West Tisbury schoolchildren at the Agricultural Hall hangs below a typed-up list of activities for an early-1930s Vineyard Haven school carnival.

There’s also a grotesquely racist 1886 advertisement for a patent medicine that was printed in the Martha’s Vineyard Herald, the newspaper owned by Mr. Strahan.

These small, but telling testaments are displayed near a gold-fringed, Union-blue commemorative ribbon for the statue’s dedication, on August 13, 1891. An enlarged photo of the dedication wraps the walls of the museum exhibit. The statue was originally placed at the foot of Circuit avenue and moved in 1930 to its current location across from the Steamship Authority ferry landing.

But while Islanders and visitors flocked to the patriotic event, the memorial had already been hit by unknown vandals, according to evidence unearthed by curatorial fellow Austin Davis.

Mr. Davis, now a junior at Princeton university, spent hundreds of hours last summer as a Sheldon Hackney Curatorial Fellow, researching Mr. Strahan and the monument, Ms. Barber said.

Among Mr. Davis’s discoveries were a pair of Herald clippings about the vandalism, which took place less than a week before the dedication when a “person or persons… cut the drapings from the Soldiers’ Memorial, and mutilated the statue on the night of Thursday [August] 6th, or early Friday morning, 7th inst.”

By researching countless archives of the Herald and the Gazette, Mr. Davis also learned how Mr. Strahan, this son of the South — born in Baltimore, later a coffee merchant in New Orleans — found his way to Martha’s Vineyard.

“We were able to connect Strahan to the Island through his in laws,” Ms. Barber said, citing a Gazette item from the 1880s. “That took weeks and weeks and hours and hours and hours of research time, to make that one connection,” she said.

Mr. Davis also created a detailed 200-year timeline, beginning in 1820, that aligns the monument’s history with that of race relations in Oak Bluffs and the nation as a whole.

“It is . . . a way to pull back the curtain on the research process,” Ms. Barber said.

Another scholar whose work is central to The Chasm is Not Closed exhibit is Oak Bluffs historian Andrew Patch, president of the Martha’s Vineyard Camp Meeting Association and a Camp Ground resident.

By poring over MVCMA records, Mr. Patch discovered a hard truth about the organization he heads: In the late 1800s, black and Wampanoag Camp Ground residents were repeatedly removed from their cabins — recorded as “shanties” — after neighbors complained, while the association continued to proclaim a policy of non-discrimination.

One of his most damning discoveries is represented in the museum show as The Purge of Wamsutta Avenue, which took place the year after the statue was dedicated and saw an entire black neighborhood eliminated.

Mr. Patch’s research, with family-by-family notes and photographs, will be published in the spring issue of the museum quarterly.

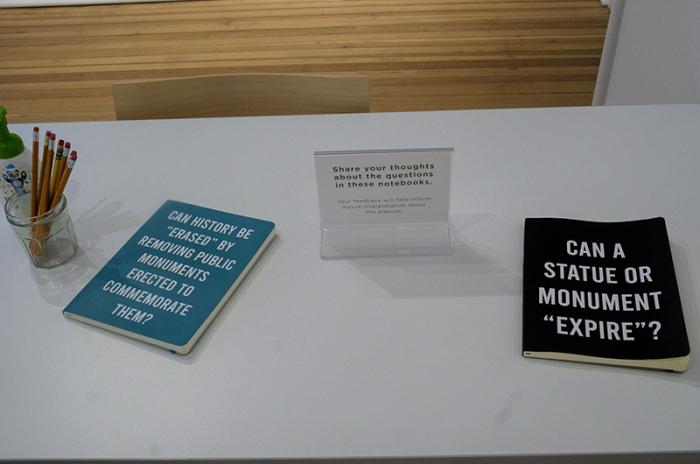

Islanders and museum visitors are invited into the process of designing the permanent exhibition, with a trio of blank notebooks and plenty of pencils for answering questions like “Can a statue or monument ‘expire’?” and “Can history be ‘erased’ by removing public monuments . . . ?”

Ms. Barber said the museum also plans public events and discussions once Covid precautions make such gatherings possible.

“We’re going to be having some evenings when we’re inviting community groups in . . . to talk about how this exhibit resonates with them,” she said. “All of that will be factored into our planning for a permanent display in the future.”

The Chasm is Not Closed is showing at the museum through April 29, Tuesday through Sunday from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m.