Arts

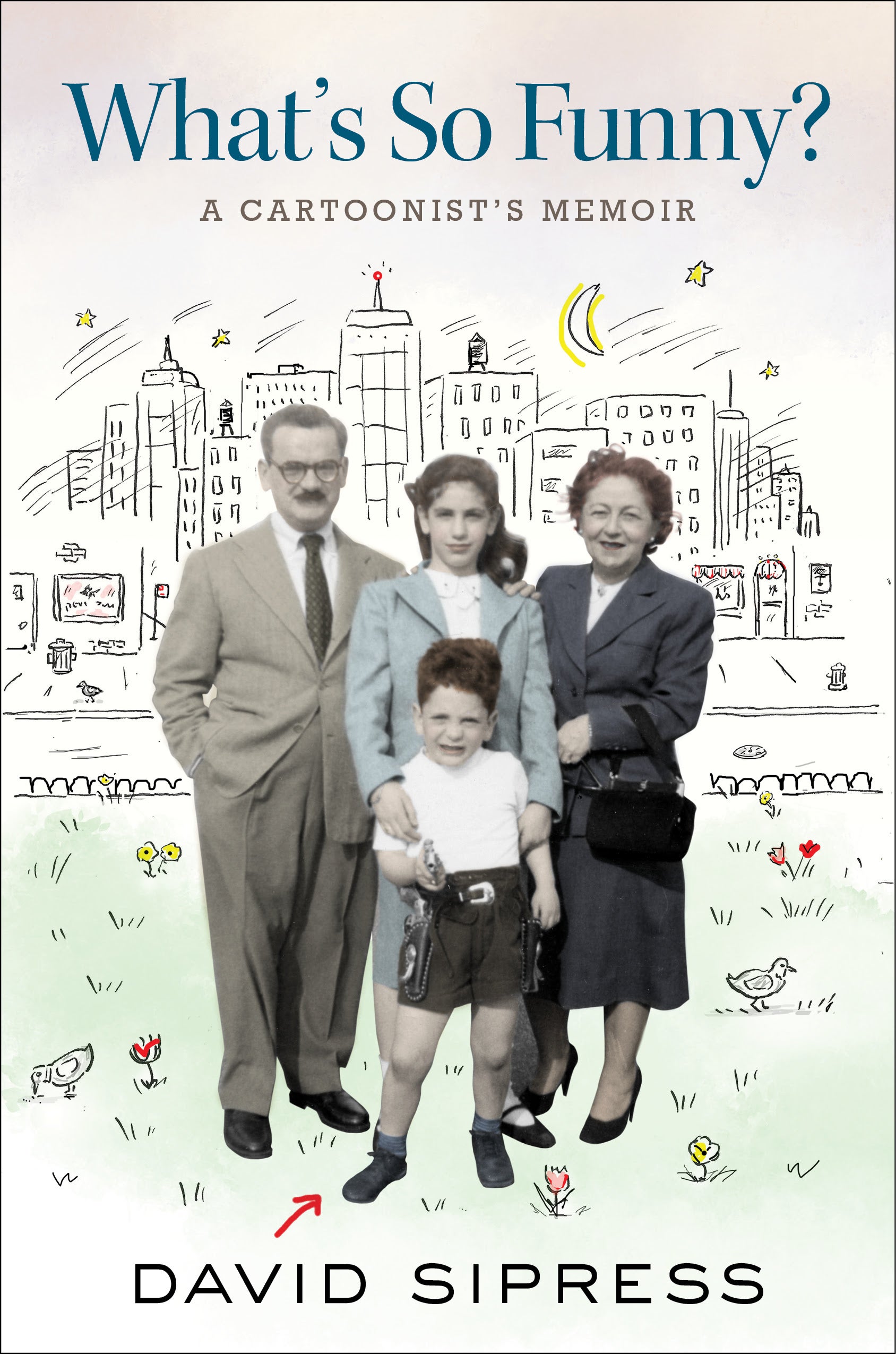

The celebrated cartoonist revisits his Boston history and his “25-year struggle” to reach his childhood dream in a new memoir, “What’s So Funny?”

At first blush, it seems like an odd combination: A guy who grew up in the heart of New York City, and an avant garde alternative newspaper covering all things Boston.

But if you picked up the legendary Boston Phoenix at all from around 1970-2000, odds are you saw the work of David Sipress, whose cartoons graced the paper’s pages every week during that decades-long stretch.

The unlikely pairing is one of the things Sipress — now one of The New Yorker magazine’s most well-known contributors — covers in “What’s So Funny?”, his new memoir that acts as something of a cartoonist’s origin story, delving into tortured family dynamics and hard-learned life lessons that can make you cringe and chuckle all at once.

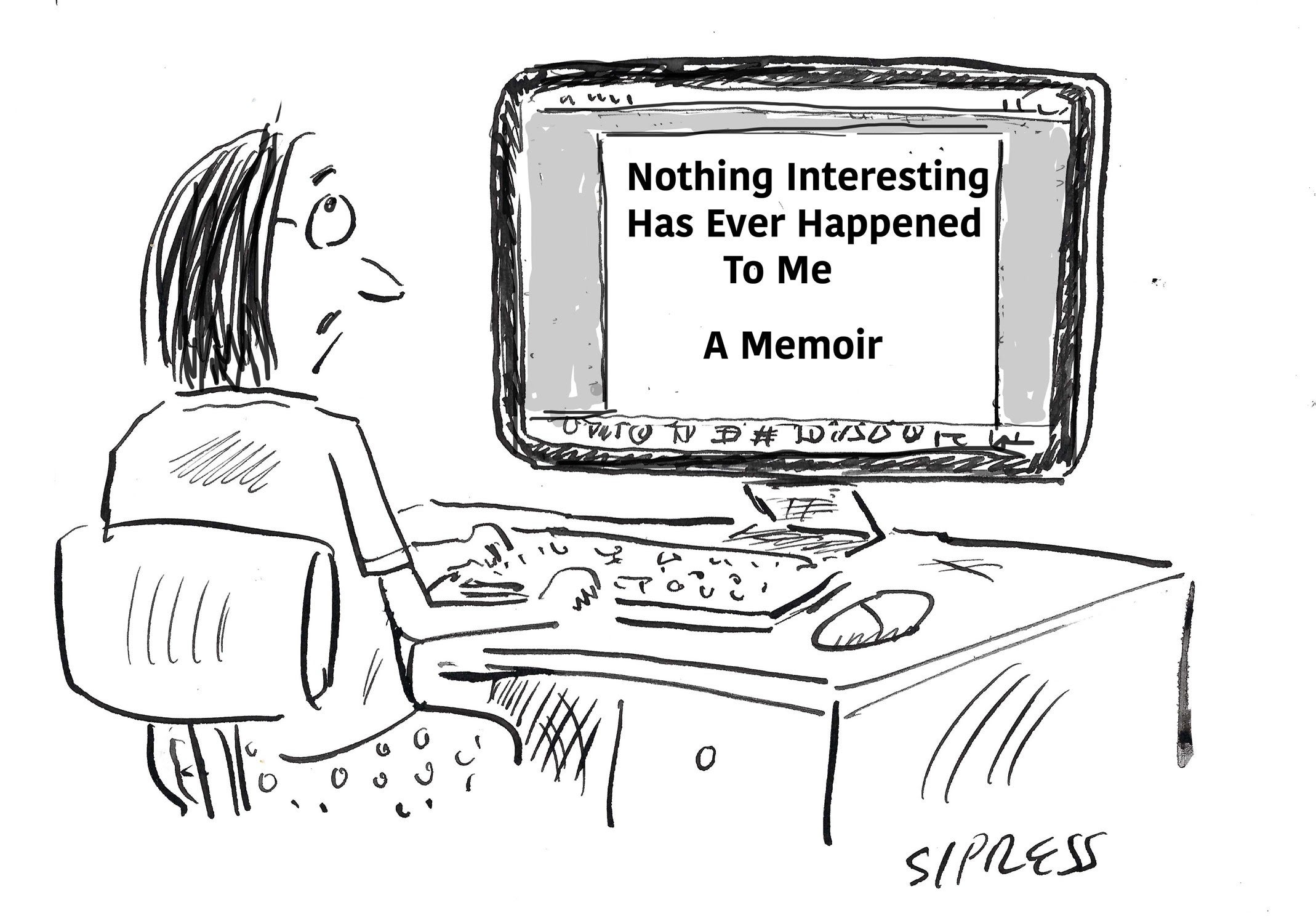

And it almost didn’t happen. “It took me forever to begin,” recalls Sipress of the book. “I did a cartoon back then for myself of a guy sitting at a computer staring at the monitor, hands ready to type, and on the monitor it says, ‘Nothing Remotely Interesting Has Ever Happened to Me: A Memoir.’ That’s where I was stuck at the beginning.”

Fortunately, Sipress, who spent 15 years in Boston and Cambridge before moving back to New York in the 1980s, eventually found his way into what became a heartfelt and enormously relatable life story — mainly by incorporating his cartoons into the process.

“I began to see that the cartoons, along with the text, were kind of a key to intensifying certain anecdotes that I tell,” he explains. “The cartoons were helpful in leavening the more disturbing and devastating aspects of anybody’s story with their family.”

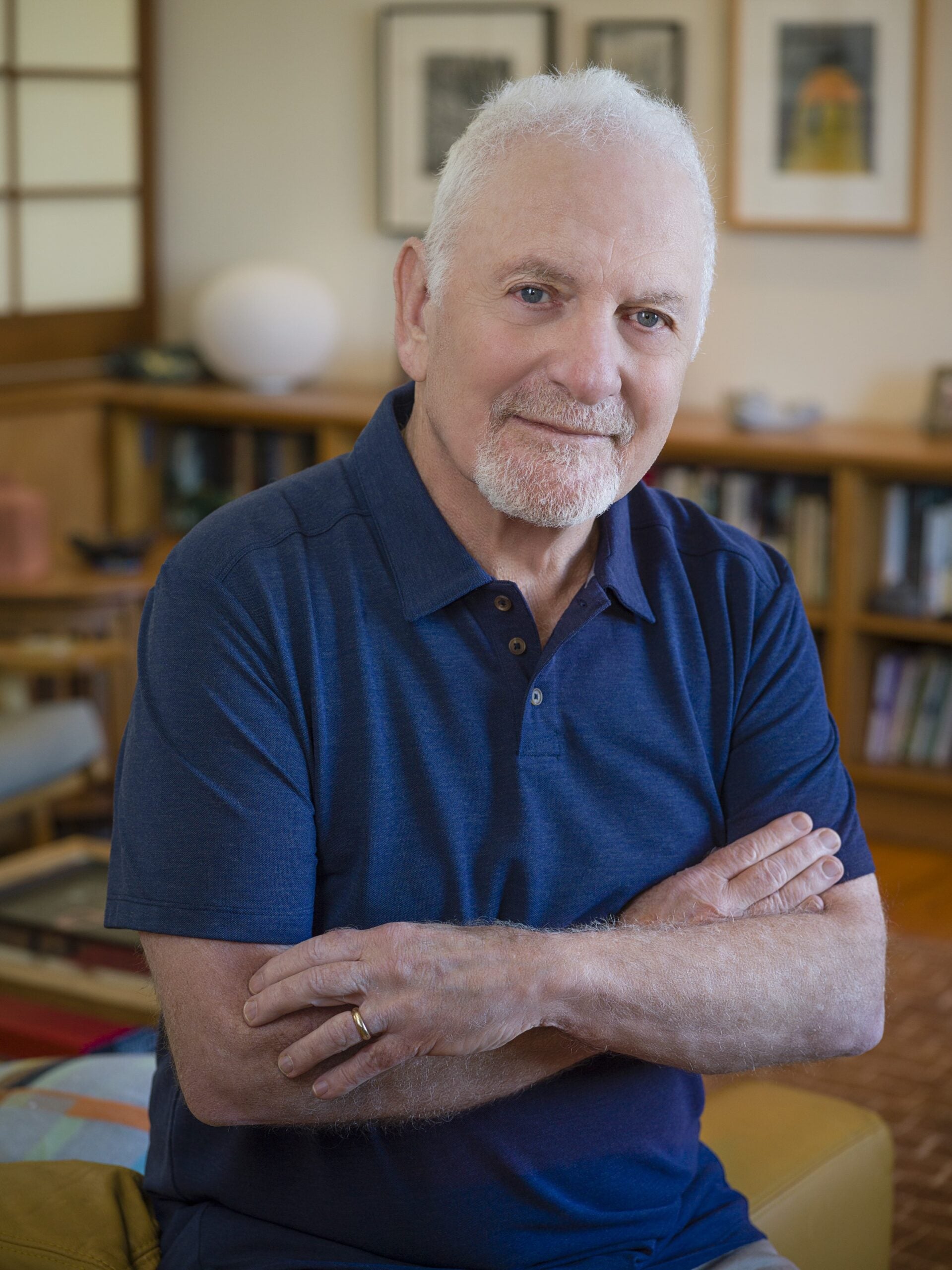

Boston.com sat down with Sipress to talk about his time in Boston and at The Phoenix, and how it led to his cartoons being shared and recognized worldwide (and even to some begrudging acceptance from his hard-nosed father).

Responses have been edited for length and clarity. Scroll down to hear the full conversation on Strip Search: The Comic Strip Podcast.

Boston.com: Can you talk a little bit about the chapter in your book about dropping out of graduate school to pursue cartooning, which was recently excerpted in The New Yorker?

David Sipress: Yeah, when I graduated from college, I went to Harvard to study in a graduate program in Soviet studies, believe it or not, and it was a real struggle and ended sort of badly. And I walked out during finals of second semester and never looked back. But it took me a while to tell my father, and that was what really terrified me, because the fact that I was there at Harvard was so important to him, and was all wrapped up in his own sense of his own success.

The excerpt that you’re talking about recounts the phone call I made about a month after I dropped out, having lied to my parents about, you know, “Classes are going great” and “I’m really learning a lot,” and meanwhile, I was wandering the streets of Cambridge trying to work up the courage to make the call.

That excerpt recounts the conversation with my father, the dialogue with my father and my mother, and it ends rather badly … My father cursed me, basically, and I … it was funny, but I still to this day, I can’t explain the reaction that I had. And yet, somehow at the time it made sense, and a little part of it makes sense to me now.

I was calling from a phone booth near Harvard Yard, and I went up to the top of Quincy Street and I looked down. I got on my bicycle and I pedaled as fast as I could, and when I reached the curb I closed my eyes, took my feet off the pedals, and glided through the oncoming traffic funneling into Harvard Square. And brakes screeched and people screamed, and I hit the curb on the other side and landed on that side of the sidewalk, and opened my eyes and, like I say in the book, the thought that went through my 22-year-old head … was, “OK, I guess I’m supposed to go on living.”

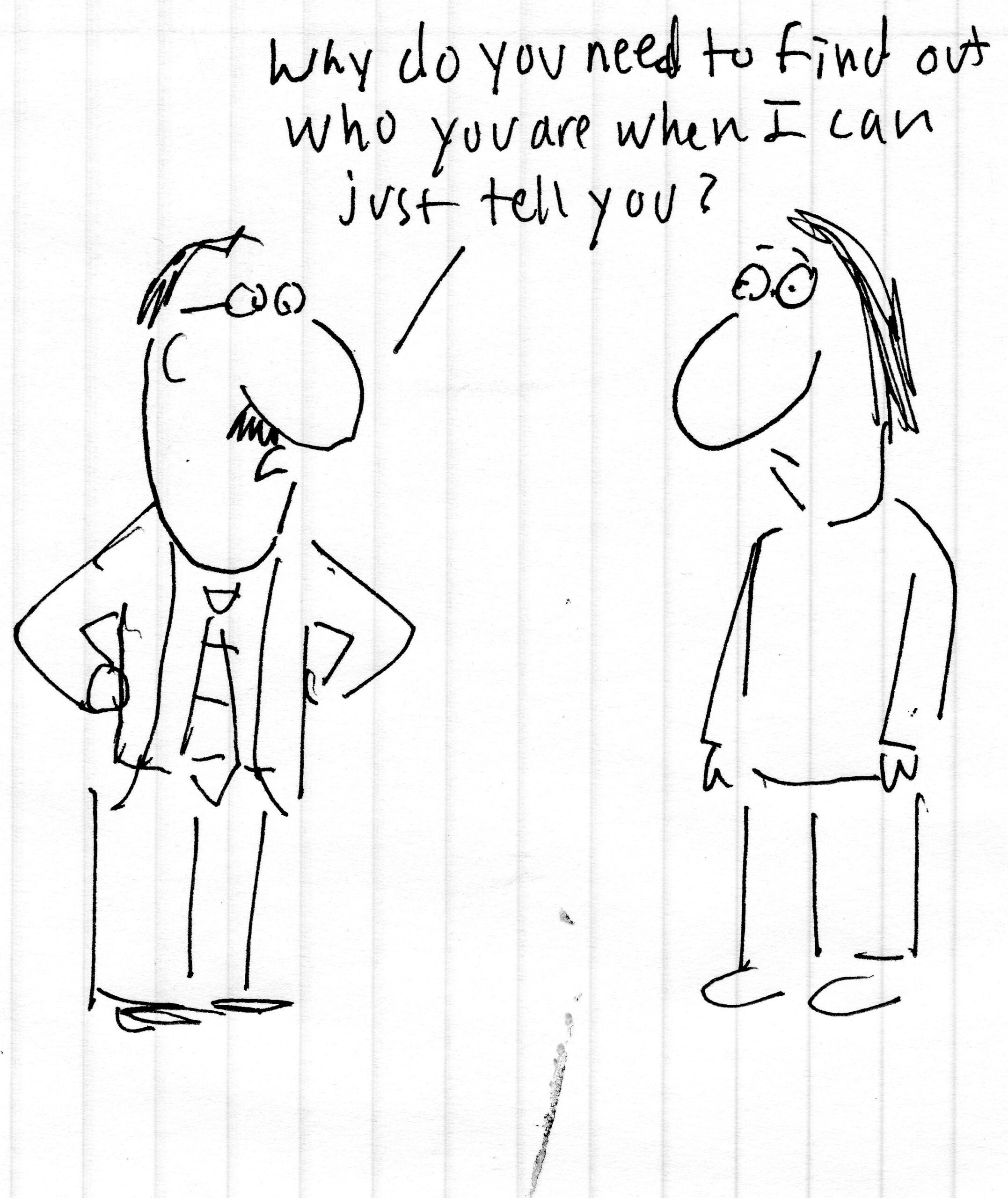

And the next thing I did was I got myself up and I went down the street to Bartley Burgers — which the fact checkers at the New Yorker tried to insist I call Mr. Bartley’s Burger Cottage, I said no, it’s Bartley Burgers — and I sat down and I had a little notebook with me, and the first thing I did was I wrote down every single word of that conversation because I knew someday I would want to revisit it. And then I drew a cartoon and the cartoon was my father and me, and my father saying to me, “Why do you need to find out who you are when I can just tell you?”

And that was that was the moment I became a cartoonist and left everything else behind. It was a lot of struggles after that, but until I told my father, I couldn’t call myself a cartoonist. Once I told my father I felt like I had stepped across the threshold.

It’s an amazing moment in the book, and I guess it couldn’t have been very long after that when you sought out the people at Boston After Dark, which would soon morph into the Boston Phoenix.

Well, I had been drawing a lot of cartoons. And I was making copies of them … and I started a totally useless business of going to Harvard Square and trying to sell Xerox copies of my cartoons for 10 cents apiece.

Do you know who Charlie Giuliano is? He was a music writer and sort of a denizen of everything hippie back then in Cambridge … I had a conversation with him; he was working at Broadside, which was another alternative paper, and my first cartoon was published in Broadside. And then I started hearing about this Boston After Dark … and one day I just got up my courage and I took my bag of Xerox copies and I went to the office.

And to my surprise the receptionist said, “Oh yeah, go right in, the editor’s right in there.” I went in and immediately smelled … it was redolent with the odor of marijuana. And to my amazement, they said, “Sure, you’re in next week.” And that was the beginning of my 30-year career of being in what then turned into the Phoenix, every single week.

And you know, I look back on that work and it’s pretty primitive in places, and somewhat different than what I do now, but I’m really proud that I was in there for that long and I added a touch of humor to that page every week.

Did you ever feel like an outsider, being a native New Yorker in enemy territory all those years?

Most definitely. I lived in Boston and Cambridge for 15 years and I made a lot of really great friends, did some interesting stuff. Not only cartoons, but I was part of something called the Graphic Workshop, a silkscreen workshop. We did posters for all the student demonstrations and then later for theaters and stuff like that.

I had a really interesting life in Boston, but I always felt like I belonged back in New York — I just couldn’t get the courage to do it, in large part because my parents were in New York, and I just didn’t know how I was going to survive being the same city as my parents at that point.

And so my time in Boston was kind of tainted with this feeling of being an outsider and being much more connected to that city to the south. But it didn’t prevent me from, you know, rooting for the Bruins and rooting for the Celtics and just loving lots of things about the city — it’s a beautiful city and it’s so much more peaceful than this place [laughs].

I noticed the Red Sox were not mentioned on that list.

Maybe you don’t know my famous Red Sox story. When I was first in the New Yorker, two or three years on, I did a cartoon — this is when the Red Sox were pretty pathetic — and it’s a guy on the psychiatrist’s couch and he’s got a Red Sox t-shirt on, and the shrink is saying to the man, “Rooting for them is a disease, Ben, it’s nothing to be ashamed of.”

That and a couple of other ones I did about the Red Sox right around that time precipitated a phone call — one day I picked up the phone and this woman said, “I’m the personal assistant to Larry Lucchino, CEO and President of the Red Sox.” She said, “He loves your cartoons about the Red Sox and he wants to invite you and your wife to Fenway Park to sit in his booth and see a game — anytime you want this summer, please just come, we’d love to meet you.”

And like an idiot I said, “Man, that’s so ironic, you know I’m an avid Yankees fan.” And there was a long silence and she said, “We’ll have to get back to you.” Last I ever heard of it.

Can you talk about how you made the transition from the Phoenix to becoming a regular at the New Yorker?

Well, what you’re calling a transition was a 25-year struggle, really. I started submitting to them not long after I started at the Phoenix and only sold my first one in 1997 — Oct. 11, I believe, 1997.

It had been my lifelong dream. I mean when I was a kid, as I say in the book, I used to draw cartoons, cut them out and paste them into my mother’s New Yorkers over the cartoons that were in there, because that was my lifelong fantasy. It just took forever and a change of editorship for me to sell my first one, and once I did it it just felt like the best thing that ever happened to me — your childhood dream comes true, it’s pretty much the best thing that’s ever happened to you.

And I learned so much just by seeing my work in that magazine. I learned what I wanted to change and improve about my drawing, what I wanted to change and improve about my ideas, and the first two or three years, there was a real learning process for me about how to make a really good, really funny cartoon.

And things have been going pretty well ever since. I have to pinch myself sometimes because I can’t believe it’s happened that way.

For the full conversation with David Sipress, including a look at his early days at The New Yorker, his influences, and his overall approach to cartooning, listen to the latest episode of Strip Search: The Comic Strip Podcast below:

Stay up-to-date on the Book Club

Catch up on the latest Boston.com Book Club pick and join the virtual author discussions.