Arts

“Art connects with us at an emotional level and a human level and touches on that empathy that’s in all of us.”

Earlier this year, when volunteers painted trees in downtown Salem bright blue for a new Peabody Essex Museum installation, a passerby remarked that the trees hadn’t always been there.

“He walked up and asked us what we were doing, as many did,” recalled Jane Winchell, the director of PEM’s Art & Nature Center and curator of Natural History. “And he said, ‘These trees weren’t here before, right?’ But the trees had been there for years, passed unnoticed by many, until they were painted blue for Konstantin Dimopoulos’s ‘The Blue Trees’ installation.”

Using a chalk-based, non-toxic pigment, Dimopoulos turns attention toward local trees to highlight the global concern of deforestation, a major contributor to climate change and biodiversity decline. His PEM installation is his 27th worldwide.

“The Blue Trees” is one of several ongoing environmental exhibits at PEM. Winchell is spearheading PEM’s new climate and environment work, and so far, she says, it’s “been a really rewarding and inspiring and empowering process to take part in.”

Other exhibits in the initiative include “Down to the Bone,” a collection of work by nature photographer Stephen Gorman and New Yorker illustrator Edward Koren, showing photos of polar bears struggling to survive in the Arctic alongside Koren’s hairy, anthropomorphic cartoon animals at the mercy of human-made climate disaster. “Climate Change: Inspiring Action” highlights climate solutions through the work of a range of contemporary artists.

Connecting art with action

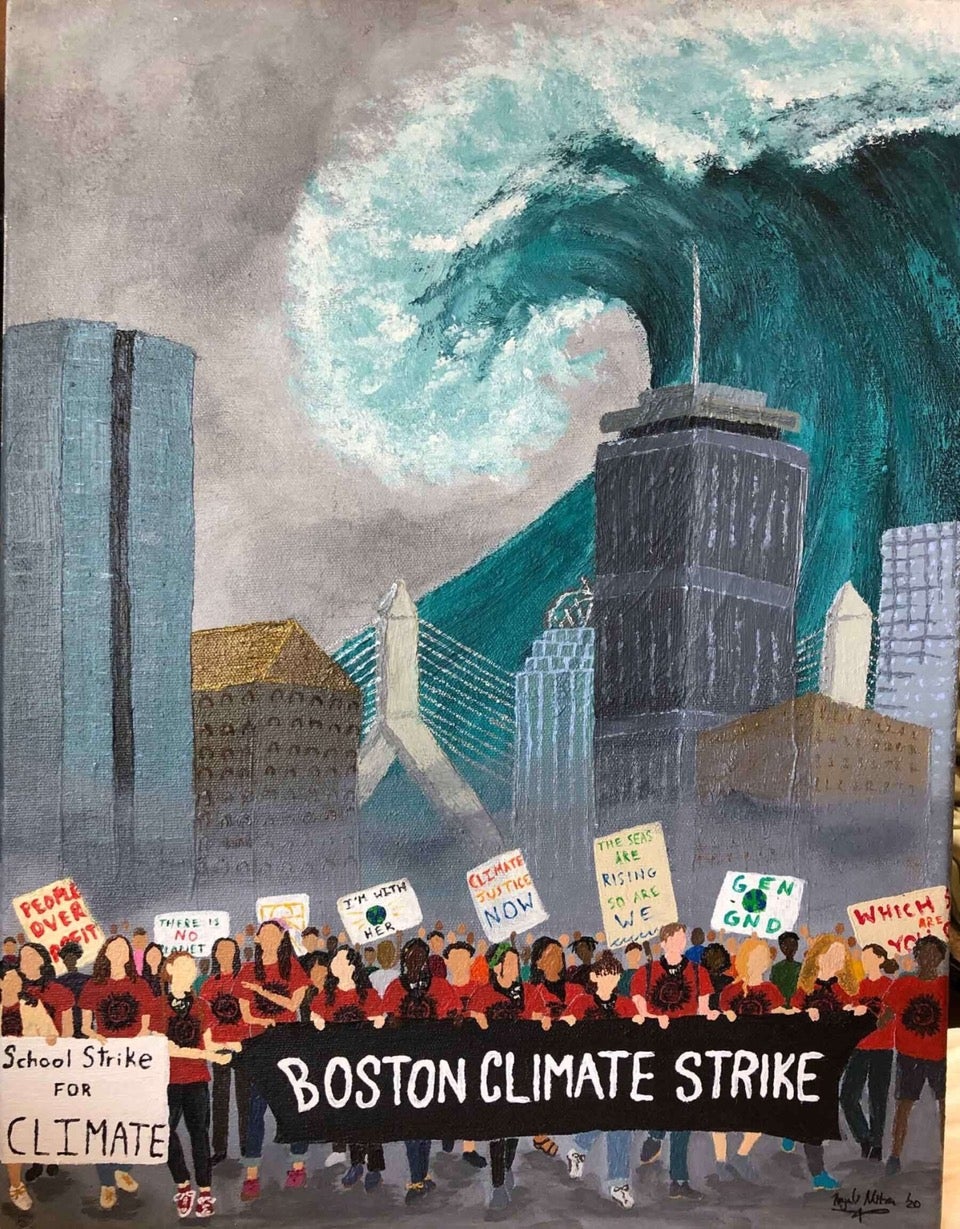

As news about the climate crisis continues to unfold around us, conversations surrounding it tend to seep into more and more facets of everyday life. Recently, police arrested 15 protesters blocking the Central Artery in Boston, disrupting the daily commute to bring attention to new fossil fuel infrastructure in Massachusetts.

“There’s been a real barrier for people talking [about the climate crisis],” said Winchell, adding that art can initiate conversations, bring climate statistics into understandable terms, and breach that barrier. “Art connects with us at an emotional level and a human level and touches on that empathy that’s in all of us,” she said.

The PEM collaborated with the Climate Museum in New York City, the first museum in the country dedicated to the climate crisis, on “Climate Change: Inspiring Action.”

“Art allows visitors to explore the impacts of climate change in community with others,” said Miranda Massie, director of the Climate Museum, “and to build resolve for taking collective action on the climate crisis.”

From devastation to inspiration

Winchell notes that sometimes, artwork about the climate crisis can feel devastating, and sometimes it can feel inspiring, and both kinds of art play a role in the climate conversation.

“Down to the Bone,” for example, she puts on the more devastating end — muddy polar bears stare hollow-eyed into the camera, next to naive cartoon animals amid the bones of their species. But the “Climate Change: Inspiring Action” exhibit sits in the adjacent room, offering viewers an opportunity to embrace a more promising future.

“We can’t have the devastating art without the balance of the works that are showing where we can go forward, how we can go forward,” said Winchell. Art plays a stripping-back role in exhibits like “Down to the Bone,” but a visionary one in “Inspiring Action.”

“Where people may be coming out of ‘Down to the Bone’ somewhat emotionally exposed, we are offering right there: this is what you can do,” said Winchell. “This is our opportunity.”

One of Winchell’s favorite environmental exhibits she’s done, “Where the Questions Live: An Exploration of Humans in Nature” by Wes Bruce, ran just before “Inspiring Action.” Bruce’s immersive, multimedia exhibit examined humans’ relationship with the natural world — and visitors loved it.

“There were so many beautiful messages left by people about … how they felt understood,” said Winchell, “and how they perceive their own relationship with nature in a new and powerful way.”

The exhibit created moments of connection with nature from inside a building — it wasn’t a walk in the woods, but it might have been even more inspiring for some visitors.

The Peabody Essex Museum is scrutinizing its own carbon footprint, too. Starting in December, they begin a three-year contract with ENGIE to get 100% of their electricity from sustainable sources like solar, wind, water, and geothermal.

With all of her climate initiatives at PEM, Winchell’s goal is to meet viewers where they’re at. “PEM is very much an accessible museum that’s focused on relevancy to people’s lives,” said Winchell, “and I hope that whenever people are coming into these exhibitions, they’re leaving having experienced something which spoke to them personally.”

More museums exploring climate change

Museums across the country are using art to help folks engage with and better understand the natural world. At the Anchorage Museum in Alaska, the director, Julie Decker, has made climate change one of the museum’s central themes, showing up in multiple exhibits.

“It’s important that museums not be episodic in how they talk about climate change,” Decker told The New York Times. “We need to make it part of our programs every day.” She also echoes Winchell’s notion that climate exhibits shouldn’t be all doom and gloom, but rather they should inspire change.

Last summer, the Museum of Fine Arts did an environmental exhibit outside — “Garden for Boston,” at the Huntington Avenue entrance, comprising a sunflower garden and a field of corn, beans, and sedges grown in the traditional Woodlands Native American method.

Massie calls the shift in more art exhibits about the environment “critical” for inspiring action.

“Art reaches diverse communities and creates a sense of agency and connection shifting our shared culture toward action on climate,” said the director of the Climate Museum.

Newsletter Signup

Stay up to date on all the latest news from Boston.com